Highlights of The World Trade Report 2024.

Category: Trade

By: Leo Kipkogei Kemboi,

The World Trade Report 2024 was launched at the start of the WTO Public Forum 2024 in Geneva titled “Trade and Inclusiveness: How to Make Trade Work for All”[1], and this blog will seek to highlight some of the most profound insights. The report delves into the crucial relationship between international trade and inclusive economic growth. It highlights the significant role trade has played in driving global income convergence and poverty reduction over recent decades. However, the report also acknowledges that progress has been uneven, with some individuals, regions, and economies lagging. The 2024 report emphasizes the need to move beyond the simplistic view of trade as a standalone solution and underscores the importance of complementary domestic policies in maximizing trade benefits for all.

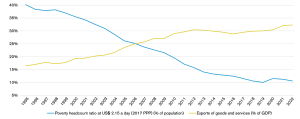

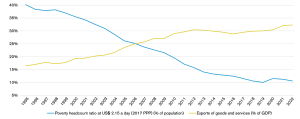

- The World Trade Report 2024 shows that there has been significant poverty reduction and greater trade openness in low- and middle-income countries, 1995-2022

Source: WTO, based on World Bank data on poverty, exports and GDP.[2]

Many economies have experienced income growth and poverty reduction without significant increases in inequality. However, global income and wealth inequality remain high. While the average Gini index fell slightly to 0.57 in 2022, large economies like China, Japan, and the United States have seen rising inequality. The top 1% currently hold 15.8% of global income, a level comparable to the early 20th century, reversing a trend of declining inequality throughout much of the 20th century. Similarly, the top 1% hold a stable but high 30.6% of global wealth.

- The World Trade Report 2024 shows there is a higher cumulative share of peaked tariff lines in lower-income economies, 1995-2023

Source: WTO, based on WTO data on applied MFN tariff data.[3]

Low-income countries, despite benefiting from WTO tariff flexibilities, exhibit greater tariff policy uncertainty. They have significantly increased applied tariffs on a larger proportion of products compared to other economies between 1995 and 2023. While this highlights the flexibility offered by the WTO, it also raises concerns about unpredictable trade policies in these nations.

- The invention of the shipping container alone has been a major driver of globalization. By 2021, it cost less to move a container from Los Angeles to Shanghai – halfway around the world – than from Los Angeles to San Diego – just 200 km down the road (Shiphub, 2021), although there is a risk that recent geopolitical and environmental disruptions may change that. The cost of overseas telecommunications is approaching zero, fuelling an explosion of digital services trade, including online education, telemedicine and online distribution. China could not have become the new “workshop of the world” without the transoceanic “conveyor belt” that containerization has provided (Economist, 2013).

- Average trade-weighted applied tariffs fell by almost 40 per cent after the Second World War and have fallen by over two-thirds in the last three decades, from 6.9 per cent in 1996 to 2 per cent in 2022. Today some 60 per cent of world trade now flows tariff-free, while another fifth is subject to tariffs of less than 5 per cent.

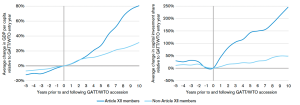

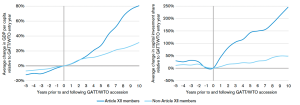

- The World Trade Report 2024 shows evidence that there is a higher economic growth in WTO members with more extensive commitments

The economic benefits of joining the World Trade Organization are linked to the depth of commitments made during the accession process. Countries joining the WTO under the stricter requirements of Article XII, which mandates significant commitments and reforms, have experienced stronger investment, GDP growth, and overall economic convergence compared to original WTO members. This suggests that embracing comprehensive reforms during WTO accession is crucial for developing economies seeking to maximize the benefits of global trade integration.

Source: WTO, based on Penn World Table and Brotto et al. (2024).[4]

- The WTO Report 2024 shows that Income convergence, particularly for developing countries, surged between 1995 and 2023 due to increased global trade. However, this progress has slowed since the 2007-08 financial crisis and reversed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately impacted poorer nations.

- The gains from trade are unevenly distributed among individuals within the economy, but this does not inherently increase inequality. The report highlights the weak correlation between trade openness and income inequality, 2021

Source: WTO, based on World Bank data on nominal GDP and real GDP per capita and WTO data on trade in goods and commercial services[5]

Conclusion

The major theme from the report is extensive evidence that international trade has been a key driver of income convergence, leading to significant income growth in developing countries. However, the report notes that the progress has been uneven, with some countries experiencing faster growth than others. The pace of convergence has also slowed in recent years, and some developing countries have been left behind. The global financial crisis of 2007-08 and the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated these existing inequalities. These events exposed the vulnerabilities of developing economies, which were often hit harder by economic shocks. They also underscored the need for more inclusive growth that benefits all segments of society. To ensure that the benefits of trade are shared more equitably, trade policies and domestic policies must work in tandem. This includes addressing issues such as high trade costs, infrastructure gaps, and limited access to technology, which disproportionately hinder developing countries. By tackling these challenges, policymakers can create a more inclusive trading system that promotes sustainable and equitable growth for all.

References

[1] WTO (2024). World Trade Report 2024: Trade and inclusiveness How to make trade work for all. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/wtr24_e/wtr24_e.pdf.

[2] According to the research, the figure depicts the evolution of the average percentage of poverty headcount at US$ 2.15 per day (2017 PPP) in population and the average share of goods and services exported in GDP for low- and middle-income nations from 1995 to 2022. The income groups are based on the 2022 World Bank classification.

[3] The figure displays the cumulative average share of the number of tariff lines increased by 15 percentage point or higher in the total number of tariff lines at the eight- or ten-digit level by income group. The income groups are based on the 2022 World Bank’s classification. The LDC group is based on the United Nations (UN) classification. Graduated LDCs include those that have graduated from LDC status and those proposed for graduation in 2026.

[4] The report indicates that the figure shows the average change in GDP per capita in relation to the year of GATT/WTO entry for both Article XII WTO members and non-Article XII members. GDP per capita growth is based on expenditure-side real GDP expressed in 2017 US$ purchasing power parity. Article XII members refers to members that acceded the WTO after 1995 under Article XII of the GATT. Non-Article XII refers to GATT contracting members that became WTO members without having to go through the Article XII process.

[5] The report notes that the figure displays the correlation between trade participation and convergence speed of economies that were low- or middle-income in 1995. The trade participation gap is the share of goods and commercial services trade in GDP, adjusted for country size, expressed as a percentage difference from the income group average. Income convergence speed is the annualized real income per capita growth between 1996 and 2021 expressed as the difference from the average growth in high-income economies. Economies below the horizontal axis did not converge in their per capita incomes towards high-income economies. Economies on the left of the vertical axis had an average trade participation below their income group average. The income groups are based on the 1995 World Bank classification. The LDC group is based on the United Nations (UN) classification

More Blogs

Tax 101: Tariffs are taxes

There is a big global debate on tariffs, their effects, and who pays for them, creating misconceptions. The broader trade strategy premised on Tariffs reflects a worldview rooted in 19th-century mercantilism, emphasizing protectionism and an aggressive use of tariffs.[1] The misconception that tariffs aren’t taxes stems from several factors. Framing plays a significant role. Tariffs […]

Law and Economics of Occupational Licensing: The Case of Law Profession

Occupational licensing is widespread in Kenya, particularly in professions such as law and medicine, and it sparks debate in law and economics. In Kenya, occupational licensing is provided for through a set of statutes. This has implications for markets of legal service provision, which we discuss in this blog. Why is occupational licensing now a […]

Mr. Trump and Kenya’s Macro

It has always been difficult to tie Mr. Trump’s statements to his subsequent policy actions. That fact qualifies any certainty in discerning his implications for Kenya’s macro now. But in three areas, the Kenyan macroeconomic authorities should be on high alert. The Kenya Shilling For much of 2024, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK)has been […]

Is Kenya’s Tax System Efficient, Optimal, and Equitable?

In my new paper, “On Efficiency, Equity, and Optimal Taxation: Reforming Kenya’s Tax System,” I examine Kenya’s tax system through the lenses of efficiency, equity, and optimality and recommend policy recommendations. I try to look at how efficiently the system generates revenue without distorting economic activity (efficiency), how fairly the tax burden is distributed across […]

Gen Z Collective Action on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Introduction The Finance Bill 2024 in Kenya sparked a wave of collective action primarily driven by Gen Z, marking a significant moment for youth engagement in Kenyan politics. This younger generation, known for their digital fluency and facing bleak economic prospects, utilised social media platforms to voice their discontent and mobilise protests against the proposed […]

Highlights of The World Trade Report 2024.

| Post date: Wed, Sep 18, 2024 |

| Category: Trade |

| By: Leo Kipkogei Kemboi, |

The World Trade Report 2024 was launched at the start of the WTO Public Forum 2024 in Geneva titled “Trade and Inclusiveness: How to Make Trade Work for All”[1], and this blog will seek to highlight some of the most profound insights. The report delves into the crucial relationship between international trade and inclusive economic growth. It highlights the significant role trade has played in driving global income convergence and poverty reduction over recent decades. However, the report also acknowledges that progress has been uneven, with some individuals, regions, and economies lagging. The 2024 report emphasizes the need to move beyond the simplistic view of trade as a standalone solution and underscores the importance of complementary domestic policies in maximizing trade benefits for all.

- The World Trade Report 2024 shows that there has been significant poverty reduction and greater trade openness in low- and middle-income countries, 1995-2022

Source: WTO, based on World Bank data on poverty, exports and GDP.[2]

Many economies have experienced income growth and poverty reduction without significant increases in inequality. However, global income and wealth inequality remain high. While the average Gini index fell slightly to 0.57 in 2022, large economies like China, Japan, and the United States have seen rising inequality. The top 1% currently hold 15.8% of global income, a level comparable to the early 20th century, reversing a trend of declining inequality throughout much of the 20th century. Similarly, the top 1% hold a stable but high 30.6% of global wealth.

- The World Trade Report 2024 shows there is a higher cumulative share of peaked tariff lines in lower-income economies, 1995-2023

Source: WTO, based on WTO data on applied MFN tariff data.[3]

Low-income countries, despite benefiting from WTO tariff flexibilities, exhibit greater tariff policy uncertainty. They have significantly increased applied tariffs on a larger proportion of products compared to other economies between 1995 and 2023. While this highlights the flexibility offered by the WTO, it also raises concerns about unpredictable trade policies in these nations.

- The invention of the shipping container alone has been a major driver of globalization. By 2021, it cost less to move a container from Los Angeles to Shanghai – halfway around the world – than from Los Angeles to San Diego – just 200 km down the road (Shiphub, 2021), although there is a risk that recent geopolitical and environmental disruptions may change that. The cost of overseas telecommunications is approaching zero, fuelling an explosion of digital services trade, including online education, telemedicine and online distribution. China could not have become the new “workshop of the world” without the transoceanic “conveyor belt” that containerization has provided (Economist, 2013).

- Average trade-weighted applied tariffs fell by almost 40 per cent after the Second World War and have fallen by over two-thirds in the last three decades, from 6.9 per cent in 1996 to 2 per cent in 2022. Today some 60 per cent of world trade now flows tariff-free, while another fifth is subject to tariffs of less than 5 per cent.

- The World Trade Report 2024 shows evidence that there is a higher economic growth in WTO members with more extensive commitments

The economic benefits of joining the World Trade Organization are linked to the depth of commitments made during the accession process. Countries joining the WTO under the stricter requirements of Article XII, which mandates significant commitments and reforms, have experienced stronger investment, GDP growth, and overall economic convergence compared to original WTO members. This suggests that embracing comprehensive reforms during WTO accession is crucial for developing economies seeking to maximize the benefits of global trade integration.

Source: WTO, based on Penn World Table and Brotto et al. (2024).[4]

- The WTO Report 2024 shows that Income convergence, particularly for developing countries, surged between 1995 and 2023 due to increased global trade. However, this progress has slowed since the 2007-08 financial crisis and reversed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately impacted poorer nations.

- The gains from trade are unevenly distributed among individuals within the economy, but this does not inherently increase inequality. The report highlights the weak correlation between trade openness and income inequality, 2021

Source: WTO, based on World Bank data on nominal GDP and real GDP per capita and WTO data on trade in goods and commercial services[5]

Conclusion

The major theme from the report is extensive evidence that international trade has been a key driver of income convergence, leading to significant income growth in developing countries. However, the report notes that the progress has been uneven, with some countries experiencing faster growth than others. The pace of convergence has also slowed in recent years, and some developing countries have been left behind. The global financial crisis of 2007-08 and the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated these existing inequalities. These events exposed the vulnerabilities of developing economies, which were often hit harder by economic shocks. They also underscored the need for more inclusive growth that benefits all segments of society. To ensure that the benefits of trade are shared more equitably, trade policies and domestic policies must work in tandem. This includes addressing issues such as high trade costs, infrastructure gaps, and limited access to technology, which disproportionately hinder developing countries. By tackling these challenges, policymakers can create a more inclusive trading system that promotes sustainable and equitable growth for all.

References

[1] WTO (2024). World Trade Report 2024: Trade and inclusiveness How to make trade work for all. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/wtr24_e/wtr24_e.pdf.

[2] According to the research, the figure depicts the evolution of the average percentage of poverty headcount at US$ 2.15 per day (2017 PPP) in population and the average share of goods and services exported in GDP for low- and middle-income nations from 1995 to 2022. The income groups are based on the 2022 World Bank classification.

[3] The figure displays the cumulative average share of the number of tariff lines increased by 15 percentage point or higher in the total number of tariff lines at the eight- or ten-digit level by income group. The income groups are based on the 2022 World Bank’s classification. The LDC group is based on the United Nations (UN) classification. Graduated LDCs include those that have graduated from LDC status and those proposed for graduation in 2026.

[4] The report indicates that the figure shows the average change in GDP per capita in relation to the year of GATT/WTO entry for both Article XII WTO members and non-Article XII members. GDP per capita growth is based on expenditure-side real GDP expressed in 2017 US$ purchasing power parity. Article XII members refers to members that acceded the WTO after 1995 under Article XII of the GATT. Non-Article XII refers to GATT contracting members that became WTO members without having to go through the Article XII process.

[5] The report notes that the figure displays the correlation between trade participation and convergence speed of economies that were low- or middle-income in 1995. The trade participation gap is the share of goods and commercial services trade in GDP, adjusted for country size, expressed as a percentage difference from the income group average. Income convergence speed is the annualized real income per capita growth between 1996 and 2021 expressed as the difference from the average growth in high-income economies. Economies below the horizontal axis did not converge in their per capita incomes towards high-income economies. Economies on the left of the vertical axis had an average trade participation below their income group average. The income groups are based on the 1995 World Bank classification. The LDC group is based on the United Nations (UN) classification

More Blogs

Tax 101: Tariffs are taxes

There is a big global debate on tariffs, their effects, and who pays for them, creating misconceptions. The broader trade strategy premised on Tariffs reflects a worldview rooted in 19th-century mercantilism, emphasizing protectionism and an aggressive use of tariffs.[1] The misconception that tariffs aren’t taxes stems from several factors. Framing plays a significant role. Tariffs […]

Law and Economics of Occupational Licensing: The Case of Law Profession

Occupational licensing is widespread in Kenya, particularly in professions such as law and medicine, and it sparks debate in law and economics. In Kenya, occupational licensing is provided for through a set of statutes. This has implications for markets of legal service provision, which we discuss in this blog. Why is occupational licensing now a […]

Mr. Trump and Kenya’s Macro

It has always been difficult to tie Mr. Trump’s statements to his subsequent policy actions. That fact qualifies any certainty in discerning his implications for Kenya’s macro now. But in three areas, the Kenyan macroeconomic authorities should be on high alert. The Kenya Shilling For much of 2024, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK)has been […]

Is Kenya’s Tax System Efficient, Optimal, and Equitable?

In my new paper, “On Efficiency, Equity, and Optimal Taxation: Reforming Kenya’s Tax System,” I examine Kenya’s tax system through the lenses of efficiency, equity, and optimality and recommend policy recommendations. I try to look at how efficiently the system generates revenue without distorting economic activity (efficiency), how fairly the tax burden is distributed across […]

Gen Z Collective Action on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Introduction The Finance Bill 2024 in Kenya sparked a wave of collective action primarily driven by Gen Z, marking a significant moment for youth engagement in Kenyan politics. This younger generation, known for their digital fluency and facing bleak economic prospects, utilised social media platforms to voice their discontent and mobilise protests against the proposed […]