How Far is Kenya from Being a Singapore for Africa?

Category: Economic DevelopmentPublic Sector Reform

By: Kwame Owino, Maureen Barasa,

In spite of the mixed results in the economic management of most countries situated in the sub-Saharan region, there remains no doubt about the ambitions of their leaders. This ambition is manifest in the characteristic admiration for the economic performance of selected countries in east Asia, Singapore included. In documents and speeches, the political leaders make statements suggesting that the success of countries in East Asia are a reflection of missed chances for sub-Saharan Africa. As the title of this article states, there is renewed optimism of selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Kenya is considered among the leading prospects for both fast economic growths, but also for structural transformation.

Regional leadership would depend on Kenya’s bearing a global orientation and an economy that draws resources and investments inwards. It is worth examining how Kenya fits the metaphor of the Singapore of Africa through its global orientation of its economic policy, the quality of government services and leading energy sector performance.

Fair comparison to Singapore requires a set of socio-economic achievement to distinguish Kenya from its peers on the sub-Saharan continent. It is a legitimate question but one that must be answered only in prospect because Kenya’s present economic achievements are modest in comparison to Singapore. Tyler Cowen, conducted this thought experiment in this unduly optimistic article in which he acknowledged risks but states that Kenya’s status as Africa’s Seventh most populous country, its geographical positioning and an economic growth rate above 5.5% per annum, more recently suggest that it is mostly likely on the journey towards being the “Singapore of Africa.

The attributes that Tyler Cowen ascribes to Kenya are real but as many as were excited by his claim as there were others who urged caution and even dismissed this article for over-exuberance on Kenya’s prospects. Bearing in mind, the importance of incomes as a sensible measure of human welfare, there are vast income differences between citizens of both countries. These material differences demonstrate that Kenya’s quest to become a sub-Saharan equivalent to Singapore ought to be viewed both with as much interest as circumspection. In 2022, the average income per citizen (Adjusted for purchasing power in US$ 2017) was measured as US$ 108,026 and US$ 4882 for Singapore and Kenya respectively.

That gap, illustrated in Chart 1 below provides reason to be careful with hasty generalization. The growth trends show a gap so wide that the scales are presented on different sides of the chart despite the fact that the variable being measured is the same (US$ equivalent in 2017). Needless to state, the growth paths in incomes is so different that a comparison is difficult to present on the same chart.

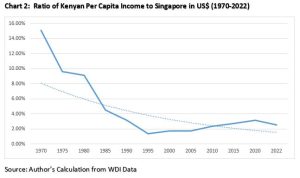

As illustrated by Chart 1, there has been a vast difference in the incomes of Kenyan and Singapore citizens for almost 50 years. In spite of that, it may be necessary to show whether there is a trend towards convergence. Chart 2 presents the trend in the average (mean) income of citizens of Kenya as a ratio of the incomes that obtain in Singapore per year. The steep decline between 1970 to 1995 confirms that Singapore’s economy provided income growth at a rate that as unmatched by Kenya. The gap started to close from 1995 to 2020 but the real income gap comparison means that Kenyan income was barely 4% of the income equivalent in Singapore by 2020.

In summary, reading Chart 1 and Chart 2 leads to the conclusion that citizens of Kenya and Singapore experienced income growth at such different levels that the ratios of their incomes changed from a Kenyan earning 16% of a Singaporean average income to less than 4%, a half century later in 2022. In other words, there has been no catch up for Kenya. So what might be pointers to the failure to catch up?

Global Orientation

To begin with, Kenya is a country that bears the demographic advantage of a young population, but distinguishable from Singapore that up to 70% of its population reside in rural areas. The labour productivity of working people in rural Kenya would need to grow immensely for this catch up to happen within a generation or less. Similar to Singapore, Kenya’s geographical position presents it with the opportunity to become the gateway into the eastern Africa interior as provider of comparatively high quality sea port, airport and logistics services for all firms situated within the East African Community (EAC). It is unclear that Kenya is capturing and making the best of this opportunity as a harbinger of international trade and logistics provision at the regional level.

The Index of Economic Freedom (IEF) is a composite measure of a country’s orientation towards a more market and price based system with government interference in the economy confined to its core roles. Here too, in 2022, Singapore’s rank as the country with the level of economic freedom, contrasts sharply with Kenya IEF ranking of 135 (Mostly Unfree). It is clear that a global orientation would be most evident in the openness of the economy and the ethos that drives the organizations of government. Yet this ranking shows that Kenya has been tentative in initiating and sustaining reforms that drive the economy decisively towards a global orientation and thus is hamstrung with slow growth in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and changes in the composition of its exports.

Singapore’s global orientation is also buttressed by the fact that this city state’s lifeline is based on its geographical position as a port city and is ranked second to the port of Shanghai in a county whose population is 250 times larger. Thus while Singapore has a favorable geographical position, it supplements that with excellent services such as logistics capability, excellent infrastructure and good regulation which makes it the most preferred transshipment facility globally. And yet Kenya’s main port in Mombasa is encumbered with inefficient practices, a cadre of domestic unions opposed to reforms and a reluctance to contract a private sector firm to manage operations more efficiently.

Government Services

As stated in the first a paragraph of this piece, many corporate and political leaders in the sub-Saharan parts of Africa are genuine admirers of Singaporean firms and public sector. In their view, the economic performance of Singapore cannot be isolated from the cooperative efforts of both. Here too, a dissection of the nature of public services provided by government would be a persuasive pointer to whether Kenya could become the Singapore of Africa. The public sector in Singapore stands out globally for low corruption, high competence, efficiency and focus on results, all due to rigorous and transparent recruitment criteria and excellent remuneration. Kenya too maintains a transparent recruitment mechanism in the public sector but the outcomes of the professional public service differ markedly, thereby affecting the pace of that growth and performance that would justify its ambition as the sub-Saharan African equivalent of Singapore.

The Fund for Peace, a global think tank produces the Public Sector Indicator (PSI), measuring the ability of a state to provide basic public goods and other essential functions. PSI is a sub-component of a composite indicator, but it specifically ranks countries on a descending scale from 10 (least efficient) to 1 (most efficient) and the average score for all countries included in 2023 was 5.45. In that edition, Singapore is ranked 165th of 179 states in the overall fragility measurement and with a PSI in joint second at 1. On the other hand, Kenya’s rank in the overall Fragile State Index is 35th with a PSI score of 8.0 against the average of 5.45. The import of these indicators suggests that Kenya’s public services delivery is below global mean and a comparison to Singapore shows the enormous strides required on Kenya’s part.

It is possible to perceive the differences in PSI scores between Singapore and Kenya as a mere result of the income gaps between the citizens of two and therefore the revenue available to the respective governments. And yet overall spending as a share of the Gross Domestic Product in 2022 was 23.49% for Kenya and 15.41% for Singapore. The significance of this is that the tax burden derived from public spending is lower for the Singapore firm and households and yet that government provides superior quality of public goods.

Electricity Generation from Renewable Sources

Kenya has successfully driven energy transition towards lower carbon alternatives in electricity production. This presents an important point for attraction of investments in clean electricity generation upon which the essential business services may be built. Kenya Investment Authority stated that by January 2023, up to 86% of Kenya’s electricity in 2022 was generated from renewable energy sources including geothermal, hydroelectric power, wind power and solar generation sources. This transition is built on the outstanding fact that Kenya is the leading nation in unlocking investments in geothermal energy in the continent and 7th in the world.

Conclusion

This blog post has examined Kenya’s preparedness to perform a regional and global role, akin to Singapore’s centrality to the economies on the Pacific region of east Asia. It confirms that the geographical advantage that Kenya bears on the eastern seaboard of the Indian Ocean will not guarantee its being an inevitable player on the African and global maritime economy. A series of changes that require reorientation towards global maritime trade, institutional engagement and proper public sector reforms are imperative for that potential to be reached. In a sense, the ambition may exist and be plainly stated, but the organizational and policy posture required to make the title of this blog post a reality remain as challenges that require astute management and a global orientation by Kenya’s public sector. Making a Singapore out of Kenya is a very tough task and worth pursuing but Kenya’s political managers should not deceive themselves. The odds appear to be very long in 2023 before the comparison to even to a Singapore of 1980s, is justifiable.

More Blogs

Tax 101: Tariffs are taxes

There is a big global debate on tariffs, their effects, and who pays for them, creating misconceptions. The broader trade strategy premised on Tariffs reflects a worldview rooted in 19th-century mercantilism, emphasizing protectionism and an aggressive use of tariffs.[1] The misconception that tariffs aren’t taxes stems from several factors. Framing plays a significant role. Tariffs […]

Law and Economics of Occupational Licensing: The Case of Law Profession

Occupational licensing is widespread in Kenya, particularly in professions such as law and medicine, and it sparks debate in law and economics. In Kenya, occupational licensing is provided for through a set of statutes. This has implications for markets of legal service provision, which we discuss in this blog. Why is occupational licensing now a […]

Mr. Trump and Kenya’s Macro

It has always been difficult to tie Mr. Trump’s statements to his subsequent policy actions. That fact qualifies any certainty in discerning his implications for Kenya’s macro now. But in three areas, the Kenyan macroeconomic authorities should be on high alert. The Kenya Shilling For much of 2024, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK)has been […]

Is Kenya’s Tax System Efficient, Optimal, and Equitable?

In my new paper, “On Efficiency, Equity, and Optimal Taxation: Reforming Kenya’s Tax System,” I examine Kenya’s tax system through the lenses of efficiency, equity, and optimality and recommend policy recommendations. I try to look at how efficiently the system generates revenue without distorting economic activity (efficiency), how fairly the tax burden is distributed across […]

Gen Z Collective Action on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Introduction The Finance Bill 2024 in Kenya sparked a wave of collective action primarily driven by Gen Z, marking a significant moment for youth engagement in Kenyan politics. This younger generation, known for their digital fluency and facing bleak economic prospects, utilised social media platforms to voice their discontent and mobilise protests against the proposed […]

How Far is Kenya from Being a Singapore for Africa?

| Post date: Fri, Aug 4, 2023 |

| Category: Economic DevelopmentPublic Sector Reform |

| By: Kwame Owino, Maureen Barasa, |

In spite of the mixed results in the economic management of most countries situated in the sub-Saharan region, there remains no doubt about the ambitions of their leaders. This ambition is manifest in the characteristic admiration for the economic performance of selected countries in east Asia, Singapore included. In documents and speeches, the political leaders make statements suggesting that the success of countries in East Asia are a reflection of missed chances for sub-Saharan Africa. As the title of this article states, there is renewed optimism of selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Kenya is considered among the leading prospects for both fast economic growths, but also for structural transformation.

Regional leadership would depend on Kenya’s bearing a global orientation and an economy that draws resources and investments inwards. It is worth examining how Kenya fits the metaphor of the Singapore of Africa through its global orientation of its economic policy, the quality of government services and leading energy sector performance.

Fair comparison to Singapore requires a set of socio-economic achievement to distinguish Kenya from its peers on the sub-Saharan continent. It is a legitimate question but one that must be answered only in prospect because Kenya’s present economic achievements are modest in comparison to Singapore. Tyler Cowen, conducted this thought experiment in this unduly optimistic article in which he acknowledged risks but states that Kenya’s status as Africa’s Seventh most populous country, its geographical positioning and an economic growth rate above 5.5% per annum, more recently suggest that it is mostly likely on the journey towards being the “Singapore of Africa.

The attributes that Tyler Cowen ascribes to Kenya are real but as many as were excited by his claim as there were others who urged caution and even dismissed this article for over-exuberance on Kenya’s prospects. Bearing in mind, the importance of incomes as a sensible measure of human welfare, there are vast income differences between citizens of both countries. These material differences demonstrate that Kenya’s quest to become a sub-Saharan equivalent to Singapore ought to be viewed both with as much interest as circumspection. In 2022, the average income per citizen (Adjusted for purchasing power in US$ 2017) was measured as US$ 108,026 and US$ 4882 for Singapore and Kenya respectively.

That gap, illustrated in Chart 1 below provides reason to be careful with hasty generalization. The growth trends show a gap so wide that the scales are presented on different sides of the chart despite the fact that the variable being measured is the same (US$ equivalent in 2017). Needless to state, the growth paths in incomes is so different that a comparison is difficult to present on the same chart.

As illustrated by Chart 1, there has been a vast difference in the incomes of Kenyan and Singapore citizens for almost 50 years. In spite of that, it may be necessary to show whether there is a trend towards convergence. Chart 2 presents the trend in the average (mean) income of citizens of Kenya as a ratio of the incomes that obtain in Singapore per year. The steep decline between 1970 to 1995 confirms that Singapore’s economy provided income growth at a rate that as unmatched by Kenya. The gap started to close from 1995 to 2020 but the real income gap comparison means that Kenyan income was barely 4% of the income equivalent in Singapore by 2020.

In summary, reading Chart 1 and Chart 2 leads to the conclusion that citizens of Kenya and Singapore experienced income growth at such different levels that the ratios of their incomes changed from a Kenyan earning 16% of a Singaporean average income to less than 4%, a half century later in 2022. In other words, there has been no catch up for Kenya. So what might be pointers to the failure to catch up?

Global Orientation

To begin with, Kenya is a country that bears the demographic advantage of a young population, but distinguishable from Singapore that up to 70% of its population reside in rural areas. The labour productivity of working people in rural Kenya would need to grow immensely for this catch up to happen within a generation or less. Similar to Singapore, Kenya’s geographical position presents it with the opportunity to become the gateway into the eastern Africa interior as provider of comparatively high quality sea port, airport and logistics services for all firms situated within the East African Community (EAC). It is unclear that Kenya is capturing and making the best of this opportunity as a harbinger of international trade and logistics provision at the regional level.

The Index of Economic Freedom (IEF) is a composite measure of a country’s orientation towards a more market and price based system with government interference in the economy confined to its core roles. Here too, in 2022, Singapore’s rank as the country with the level of economic freedom, contrasts sharply with Kenya IEF ranking of 135 (Mostly Unfree). It is clear that a global orientation would be most evident in the openness of the economy and the ethos that drives the organizations of government. Yet this ranking shows that Kenya has been tentative in initiating and sustaining reforms that drive the economy decisively towards a global orientation and thus is hamstrung with slow growth in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and changes in the composition of its exports.

Singapore’s global orientation is also buttressed by the fact that this city state’s lifeline is based on its geographical position as a port city and is ranked second to the port of Shanghai in a county whose population is 250 times larger. Thus while Singapore has a favorable geographical position, it supplements that with excellent services such as logistics capability, excellent infrastructure and good regulation which makes it the most preferred transshipment facility globally. And yet Kenya’s main port in Mombasa is encumbered with inefficient practices, a cadre of domestic unions opposed to reforms and a reluctance to contract a private sector firm to manage operations more efficiently.

Government Services

As stated in the first a paragraph of this piece, many corporate and political leaders in the sub-Saharan parts of Africa are genuine admirers of Singaporean firms and public sector. In their view, the economic performance of Singapore cannot be isolated from the cooperative efforts of both. Here too, a dissection of the nature of public services provided by government would be a persuasive pointer to whether Kenya could become the Singapore of Africa. The public sector in Singapore stands out globally for low corruption, high competence, efficiency and focus on results, all due to rigorous and transparent recruitment criteria and excellent remuneration. Kenya too maintains a transparent recruitment mechanism in the public sector but the outcomes of the professional public service differ markedly, thereby affecting the pace of that growth and performance that would justify its ambition as the sub-Saharan African equivalent of Singapore.

The Fund for Peace, a global think tank produces the Public Sector Indicator (PSI), measuring the ability of a state to provide basic public goods and other essential functions. PSI is a sub-component of a composite indicator, but it specifically ranks countries on a descending scale from 10 (least efficient) to 1 (most efficient) and the average score for all countries included in 2023 was 5.45. In that edition, Singapore is ranked 165th of 179 states in the overall fragility measurement and with a PSI in joint second at 1. On the other hand, Kenya’s rank in the overall Fragile State Index is 35th with a PSI score of 8.0 against the average of 5.45. The import of these indicators suggests that Kenya’s public services delivery is below global mean and a comparison to Singapore shows the enormous strides required on Kenya’s part.

It is possible to perceive the differences in PSI scores between Singapore and Kenya as a mere result of the income gaps between the citizens of two and therefore the revenue available to the respective governments. And yet overall spending as a share of the Gross Domestic Product in 2022 was 23.49% for Kenya and 15.41% for Singapore. The significance of this is that the tax burden derived from public spending is lower for the Singapore firm and households and yet that government provides superior quality of public goods.

Electricity Generation from Renewable Sources

Kenya has successfully driven energy transition towards lower carbon alternatives in electricity production. This presents an important point for attraction of investments in clean electricity generation upon which the essential business services may be built. Kenya Investment Authority stated that by January 2023, up to 86% of Kenya’s electricity in 2022 was generated from renewable energy sources including geothermal, hydroelectric power, wind power and solar generation sources. This transition is built on the outstanding fact that Kenya is the leading nation in unlocking investments in geothermal energy in the continent and 7th in the world.

Conclusion

This blog post has examined Kenya’s preparedness to perform a regional and global role, akin to Singapore’s centrality to the economies on the Pacific region of east Asia. It confirms that the geographical advantage that Kenya bears on the eastern seaboard of the Indian Ocean will not guarantee its being an inevitable player on the African and global maritime economy. A series of changes that require reorientation towards global maritime trade, institutional engagement and proper public sector reforms are imperative for that potential to be reached. In a sense, the ambition may exist and be plainly stated, but the organizational and policy posture required to make the title of this blog post a reality remain as challenges that require astute management and a global orientation by Kenya’s public sector. Making a Singapore out of Kenya is a very tough task and worth pursuing but Kenya’s political managers should not deceive themselves. The odds appear to be very long in 2023 before the comparison to even to a Singapore of 1980s, is justifiable.

More Blogs

Tax 101: Tariffs are taxes

There is a big global debate on tariffs, their effects, and who pays for them, creating misconceptions. The broader trade strategy premised on Tariffs reflects a worldview rooted in 19th-century mercantilism, emphasizing protectionism and an aggressive use of tariffs.[1] The misconception that tariffs aren’t taxes stems from several factors. Framing plays a significant role. Tariffs […]

Law and Economics of Occupational Licensing: The Case of Law Profession

Occupational licensing is widespread in Kenya, particularly in professions such as law and medicine, and it sparks debate in law and economics. In Kenya, occupational licensing is provided for through a set of statutes. This has implications for markets of legal service provision, which we discuss in this blog. Why is occupational licensing now a […]

Mr. Trump and Kenya’s Macro

It has always been difficult to tie Mr. Trump’s statements to his subsequent policy actions. That fact qualifies any certainty in discerning his implications for Kenya’s macro now. But in three areas, the Kenyan macroeconomic authorities should be on high alert. The Kenya Shilling For much of 2024, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK)has been […]

Is Kenya’s Tax System Efficient, Optimal, and Equitable?

In my new paper, “On Efficiency, Equity, and Optimal Taxation: Reforming Kenya’s Tax System,” I examine Kenya’s tax system through the lenses of efficiency, equity, and optimality and recommend policy recommendations. I try to look at how efficiently the system generates revenue without distorting economic activity (efficiency), how fairly the tax burden is distributed across […]

Gen Z Collective Action on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Introduction The Finance Bill 2024 in Kenya sparked a wave of collective action primarily driven by Gen Z, marking a significant moment for youth engagement in Kenyan politics. This younger generation, known for their digital fluency and facing bleak economic prospects, utilised social media platforms to voice their discontent and mobilise protests against the proposed […]