The Grounds to Repeal the Price Control Act of 2011

Category: Economic literacy

By: Leo Kipkogei Kemboi,

The Price Control Act of 2011, with its imposition of price ceilings on essential goods, represents a significant intervention in the natural forces of supply and demand that govern a free market. The Act empowers the Minister to control the prices of essential goods, preventing them from becoming unaffordable. The Act outlines a specific mechanism for price control. First, the Minister can declare any goods as “essential commodities” through an official order published in the Gazette, the official government publication. Following this declaration, the Minister, in consultation with the relevant industry, sets the maximum price at which these essential commodities can be sold. The Act also includes enforcement provisions outlining penalties for selling and purchasing essential commodities above the established maximum price.

Key features of the Act include a significant degree of Ministerial Discretion. The Act grants the Minister considerable power to determine which goods are classified as “essential” and set their corresponding maximum prices. Additionally, the Act allows for Geographic Variation, enabling different maximum prices for various areas within Kenya. This flexibility accounts for regional variations in supply, demand, and costs associated with essential commodities.

Price controls exemplify a crucial intersection of law, economics, and individual liberties. These policies directly intervene in the free market by granting governments the legal authority to dictate prices, impacting producers and consumers. While often intended to ensure affordability, price controls can distort market signals, leading to unintended consequences such as shortages, reduced innovation, and black markets. This intervention raises concerns about economic freedom, as businesses face limitations on their ability to set prices, and consumers may experience restricted choices in the marketplace. Therefore, the debate over price controls hinges on balancing government intervention with the principles of a free-market economy and preserving economic liberties.

Price controls are implemented for either ceilings or floors. Ceilings cap prices to increase affordability, such as rent control, price limits on necessities during emergencies, and drug price regulations. Floors set minimum prices, as seen with minimum wage laws, intending to support incomes[1].

While striving to make crucial goods more affordable, this intervention has led to unintended consequences that have ultimately harmed the market efficiency and the consumers it sought to protect.

The grounds for why the Price Control Act of 2011 should be repealed are listed as follows

- The Ineffectiveness of Price Ceilings in Achieving Efficient Markets

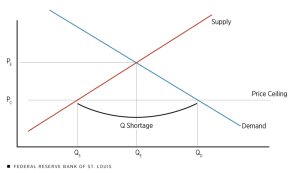

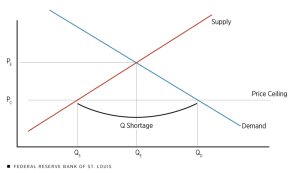

In a free market, prices act as indicators of scarcity and desirability. When artificial price ceilings are set below the equilibrium price, demand inevitably outstrips supply. This occurs because the lower price encourages consumption while simultaneously discouraging production, leading to shortages, as shown in the chart below.

Chart 1: Supply and Demand with a Price Ceiling

Source: (Neely, 2022)

An example of how such previous price control schemes have paned is how Kenyan supermarkets in 2022were rationing maize flour to a maximum of four packets per customer due to panic buying, and this follows a government directive reducing maize flour prices to KSh 100 under a four-week subsidy.[2]

Producers, faced with diminished profit margins, are less likely to invest in expanding production or improving efficiency. This lack of investment can stifle innovation and cause stagnation within the essential goods market.Guénette (2020) notes that price controls can dampen investment and growth, worsen poverty outcomes, cause countries to incur heavy fiscal burdens, and complicate the effective conduct of monetary policy.[3]

Price ceilings also disrupt the efficient allocation of resources. Shortages often necessitate rationing mechanisms, which are rarely equitable or efficient. Instead of goods being allocated based on willingness to pay, systems like first-come-first-served, lotteries, or even favouritism can emerge, leading to unfair access. Moreover, a price ceiling creates a breeding ground for black markets. Unable to profit legally, sellers are incentivized to operate outside the law, selling goods above the mandated price. This undermines the Act’s purpose and exposes consumers to exploitation.

The trade-off between equity and efficiency is central to the issue of price controls. While the Act aspires to promote equity by making essential goods more affordable, this comes at the expense of economic efficiency. Price ceilings inevitably create a deadweight loss, representing a loss of potential societal welfare. This loss occurs because transactions that would have been mutually beneficial at the equilibrium price are no longer possible.

Another example of price control schemes that failed include the interest rate cap, a price ceiling, even though enforced outside the Act, led to detrimental effects. Fengler (2012) notes that while Kenyan borrowers have recently seen the removal of price controls on loans, concerns about interest rate caps persist. Despite the Kenyan parliament’s passage of a new finance bill that avoids such caps, many policymakers and citizens believe interest rates should be regulated, particularly given their sharp rise since late 2011. This sentiment stems from the impact of high prices on consumers. Borrowers, in particular, continue to express a strong desire for more affordable loan options.[4]

- Price ceilings have unintended consequences and long-term effects.

While price controls might appear as a simple solution for ensuring affordability, they frequently lead to unintended consequences that harm producers and consumers, especially over the long term. Price ceilings can significantly discourage producers of essential goods. When prices are artificially capped below the market equilibrium, producers face reduced profit margins, making it less appealing to maintain or increase production. This can lead to shortages and reduced availability of essential goods. Additionally, facing limited profitability, producers are less likely to invest in research and development, technological upgrades, or capacity expansion, ultimately stifling innovation and potentially causing the quality of essential goods to stagnate or decline. In extreme cases, prolonged price controls and associated challenges can force producers to exit the market altogether, reducing competition and limiting essential goods’ availability and diversity.

Furthermore, price ceilings often create an environment ripe for the growth of black markets and informal economic activities. The artificial price difference between the controlled and market-clearing prices creates a strong incentive for illegal actors to procure goods and sell them at a premium in unregulated markets. By their very nature, Black markets thrive on circumventing regulations and legal frameworks, making monitoring and controlling transactions’ quality, safety, and fairness difficult. This proliferation of black markets undermines legitimate businesses that comply with regulations and pay taxes, creating an uneven playing field and potentially harming the overall economy.

Ironically, while intended to protect consumers, price controls can harm them in the long run. As production decreases and producers exit the market, consumers face limited choices and might struggle to find the essential goods they need. With reduced profitability, producers might cut corners on quality to maintain some profit margin, leading to a decline in the quality and safety of essential goods. Consumers might also pay more than the official price ceiling through black markets or incur additional costs associated with searching for scarce goods.

- The Challenges of Price Control in Government Intervention and Regulatory Burden

Government intervention in markets, mainly through price controls, often faces significant challenges and unintended consequences despite well-intentioned goals. One fundamental issue is information asymmetry. Information asymmetry, often called “information failure,” arises in economic transactions when one party holds more significant knowledge than the other, and this imbalance typically occurs when the seller of a product or service knows more than the buyer. [5] Governments rarely possess the comprehensive and nuanced market knowledge to accurately determine the “correct” price for essential goods across diverse and dynamic markets. These markets are incredibly complex, with fluctuating prices based on countless factors like supply and demand dynamics, input costs, seasonality, and consumer preferences. Accurately accounting for all these variables to set an artificial price is a daunting, if not impossible, task. Setting prices too low can discourage production and lead to shortages, while setting them too high might not provide meaningful relief for consumers. The constantly evolving nature of markets further complicates this delicate balancing act.

Implementing and enforcing price controls inevitably creates an administrative burden on governments. Resources are required to monitor markets, identify violations, and penalize those who circumvent price ceilings. This enforcement can strain government budgets and divert resources from other essential services. Additionally, price controls often fuel the growth of black markets, where goods are traded illegally at prices above the mandated ceilings. This necessitates further enforcement efforts, creating a vicious regulation and illicit activity cycle.

Price controls can create significant uncertainty for investors providing goods and services. The prospect of government intervention in pricing can deter investment in essential sectors as investors seek stability and predictability. When price ceilings constrain profits, companies have less incentive to innovate or invest in research and development. This can hinder technological advancements and limit the availability of new and improved products.

What are the other policy options for price controls in Kenya?

While the Price Control Act of 2011 aims to ensure the affordability of essential goods, its reliance on setting maximum prices can lead to market distortions. Exploring alternative policy options might offer more sustainable and less disruptive solutions. One such alternative is targeted subsidies. Instead of blanket price controls that impact the entire market, targeted subsidies directed at low-income households could prove more efficient. This approach directly assists those in need, ensuring affordability without unintended consequences for others. Targeted subsidies maintain market efficiency by allowing prices to fluctuate based on supply and demand, incentivizing production, and discouraging shortages. Additionally, this method can be more cost-effective than broad price controls, as government expenditure is focused on vulnerable populations.

Another alternative is promoting competition within essential goods sectors. Fostering a competitive landscape can naturally moderate prices and give consumers more choices. A competitive market incentivizes businesses to offer competitive prices to attract customers, indirectly achieving the Act’s goal of reasonable prices. This market-driven solution relies on natural forces to regulate prices, reducing the need for artificial controls. Moreover, competition encourages businesses to innovate, improve efficiency, and offer better quality goods and services, ultimately benefiting consumers with more excellent choices and bargaining power.

Instead of treating the symptom (high prices) with price controls, focus on the root causes of supply-side constraints and offer a more sustainable solution. Prices can stabilize naturally by boosting supply and addressing bottlenecks, increasing availability and affordability in the long run. This approach addresses the reasons for high prices, leading to more lasting solutions. Furthermore, investing in infrastructure, logistics, or technology to improve supply chains can positively impact economic growth.

End Notes

[1] Neely, Christopher. “Why Price Controls Should Stay in the History Books.” Www.stlouisfed.org, 24 Mar. 2022, www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/2022/mar/why-price-controls-should-stay-history-books.

[2] Andae, Gerald. “Supermarkets Ration Sh100 Maize Flour Purchases on Buying Stampede.” Business Daily, Business Daily, 21 July 2022, www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/markets/commodities/supermarkets-ration-sh100-maize-flour-purchases-3887744

[3] Guénette, Justin-Damien. Price Controls Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes. 2020, documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/735161586781898890/pdf/Price-Controls-Good-Intentions-Bad-Outcomes.pdf.

[4] Fengler, Wolfgang. “How Price Controls Can Lead to Higher Prices.” World Bank Blogs, 2024, blogs.worldbank.org/en/africacan/how-price-controls-can-lead-to-higher-prices.

[5] Bloomenthal, Andrew. “Asymmetric Information in Economics Explained.” Investopedia, 19 Jan. 2021, www.investopedia.com/terms/a/asymmetricinformation.asp.

More Blogs

Gen Z Collective Action on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Introduction The Finance Bill 2024 in Kenya sparked a wave of collective action primarily driven by Gen Z, marking a significant moment for youth engagement in Kenyan politics. This younger generation, known for their digital fluency and facing bleak economic prospects, utilised social media platforms to voice their discontent and mobilise protests against the proposed […]

Two Immediate Monetary-Framework Imperatives for Mr. Mbadi

The credibility of Monetary Policy in Kenya is compromised at present by two factors: As we anticipated mid-year, inflation is headed below the target range for the first time; The 7-member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has four vacancies. In light of the former prospect, the MPC reduced the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) Policy Rate, […]

Important dates and Citizen Concerns During Budget Planning Phase for Fiscal Year 2025/2026

The Budget formulation and preparation process in Kenya is guided by a budget calendar which indicates the timelines for key activities issued in accordance with Section 36 of the Public Finance Management Act, 2012.These provide guidelines on the procedures for preparing the subsequent financial year and the Medium-Term budget forecasts. The Launch of the budget […]

Adjusted IMF Program Demands on Kenya

In the IMF WEO published yesterday, the IMF elaborated its macroeconomic framework for the ongoing IMF program. The numbers clarify how the program, derailed by the mid-year Gen-Z protests, has been adjusted to make possible the Board meeting for the combined 7th and 8th Reviews scheduled for October 30. The adjustments, unfortunately, again raise profound […]

What does the Nobel Prize in Economics 2024 mean for Constitution Implementation in Kenya?

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for their research on how a country’s institutions significantly impact its long-term economic success.[1] Their work emphasizes that it’s not just about a nation’s resources or technological advancements but rather the “rules of the game” that truly matter. Countries with […]

The Grounds to Repeal the Price Control Act of 2011

| Post date: Tue, Sep 10, 2024 |

| Category: Economic literacy |

| By: Leo Kipkogei Kemboi, |

The Price Control Act of 2011, with its imposition of price ceilings on essential goods, represents a significant intervention in the natural forces of supply and demand that govern a free market. The Act empowers the Minister to control the prices of essential goods, preventing them from becoming unaffordable. The Act outlines a specific mechanism for price control. First, the Minister can declare any goods as “essential commodities” through an official order published in the Gazette, the official government publication. Following this declaration, the Minister, in consultation with the relevant industry, sets the maximum price at which these essential commodities can be sold. The Act also includes enforcement provisions outlining penalties for selling and purchasing essential commodities above the established maximum price.

Key features of the Act include a significant degree of Ministerial Discretion. The Act grants the Minister considerable power to determine which goods are classified as “essential” and set their corresponding maximum prices. Additionally, the Act allows for Geographic Variation, enabling different maximum prices for various areas within Kenya. This flexibility accounts for regional variations in supply, demand, and costs associated with essential commodities.

Price controls exemplify a crucial intersection of law, economics, and individual liberties. These policies directly intervene in the free market by granting governments the legal authority to dictate prices, impacting producers and consumers. While often intended to ensure affordability, price controls can distort market signals, leading to unintended consequences such as shortages, reduced innovation, and black markets. This intervention raises concerns about economic freedom, as businesses face limitations on their ability to set prices, and consumers may experience restricted choices in the marketplace. Therefore, the debate over price controls hinges on balancing government intervention with the principles of a free-market economy and preserving economic liberties.

Price controls are implemented for either ceilings or floors. Ceilings cap prices to increase affordability, such as rent control, price limits on necessities during emergencies, and drug price regulations. Floors set minimum prices, as seen with minimum wage laws, intending to support incomes[1].

While striving to make crucial goods more affordable, this intervention has led to unintended consequences that have ultimately harmed the market efficiency and the consumers it sought to protect.

The grounds for why the Price Control Act of 2011 should be repealed are listed as follows

- The Ineffectiveness of Price Ceilings in Achieving Efficient Markets

In a free market, prices act as indicators of scarcity and desirability. When artificial price ceilings are set below the equilibrium price, demand inevitably outstrips supply. This occurs because the lower price encourages consumption while simultaneously discouraging production, leading to shortages, as shown in the chart below.

Chart 1: Supply and Demand with a Price Ceiling

Source: (Neely, 2022)

An example of how such previous price control schemes have paned is how Kenyan supermarkets in 2022were rationing maize flour to a maximum of four packets per customer due to panic buying, and this follows a government directive reducing maize flour prices to KSh 100 under a four-week subsidy.[2]

Producers, faced with diminished profit margins, are less likely to invest in expanding production or improving efficiency. This lack of investment can stifle innovation and cause stagnation within the essential goods market.Guénette (2020) notes that price controls can dampen investment and growth, worsen poverty outcomes, cause countries to incur heavy fiscal burdens, and complicate the effective conduct of monetary policy.[3]

Price ceilings also disrupt the efficient allocation of resources. Shortages often necessitate rationing mechanisms, which are rarely equitable or efficient. Instead of goods being allocated based on willingness to pay, systems like first-come-first-served, lotteries, or even favouritism can emerge, leading to unfair access. Moreover, a price ceiling creates a breeding ground for black markets. Unable to profit legally, sellers are incentivized to operate outside the law, selling goods above the mandated price. This undermines the Act’s purpose and exposes consumers to exploitation.

The trade-off between equity and efficiency is central to the issue of price controls. While the Act aspires to promote equity by making essential goods more affordable, this comes at the expense of economic efficiency. Price ceilings inevitably create a deadweight loss, representing a loss of potential societal welfare. This loss occurs because transactions that would have been mutually beneficial at the equilibrium price are no longer possible.

Another example of price control schemes that failed include the interest rate cap, a price ceiling, even though enforced outside the Act, led to detrimental effects. Fengler (2012) notes that while Kenyan borrowers have recently seen the removal of price controls on loans, concerns about interest rate caps persist. Despite the Kenyan parliament’s passage of a new finance bill that avoids such caps, many policymakers and citizens believe interest rates should be regulated, particularly given their sharp rise since late 2011. This sentiment stems from the impact of high prices on consumers. Borrowers, in particular, continue to express a strong desire for more affordable loan options.[4]

- Price ceilings have unintended consequences and long-term effects.

While price controls might appear as a simple solution for ensuring affordability, they frequently lead to unintended consequences that harm producers and consumers, especially over the long term. Price ceilings can significantly discourage producers of essential goods. When prices are artificially capped below the market equilibrium, producers face reduced profit margins, making it less appealing to maintain or increase production. This can lead to shortages and reduced availability of essential goods. Additionally, facing limited profitability, producers are less likely to invest in research and development, technological upgrades, or capacity expansion, ultimately stifling innovation and potentially causing the quality of essential goods to stagnate or decline. In extreme cases, prolonged price controls and associated challenges can force producers to exit the market altogether, reducing competition and limiting essential goods’ availability and diversity.

Furthermore, price ceilings often create an environment ripe for the growth of black markets and informal economic activities. The artificial price difference between the controlled and market-clearing prices creates a strong incentive for illegal actors to procure goods and sell them at a premium in unregulated markets. By their very nature, Black markets thrive on circumventing regulations and legal frameworks, making monitoring and controlling transactions’ quality, safety, and fairness difficult. This proliferation of black markets undermines legitimate businesses that comply with regulations and pay taxes, creating an uneven playing field and potentially harming the overall economy.

Ironically, while intended to protect consumers, price controls can harm them in the long run. As production decreases and producers exit the market, consumers face limited choices and might struggle to find the essential goods they need. With reduced profitability, producers might cut corners on quality to maintain some profit margin, leading to a decline in the quality and safety of essential goods. Consumers might also pay more than the official price ceiling through black markets or incur additional costs associated with searching for scarce goods.

- The Challenges of Price Control in Government Intervention and Regulatory Burden

Government intervention in markets, mainly through price controls, often faces significant challenges and unintended consequences despite well-intentioned goals. One fundamental issue is information asymmetry. Information asymmetry, often called “information failure,” arises in economic transactions when one party holds more significant knowledge than the other, and this imbalance typically occurs when the seller of a product or service knows more than the buyer. [5] Governments rarely possess the comprehensive and nuanced market knowledge to accurately determine the “correct” price for essential goods across diverse and dynamic markets. These markets are incredibly complex, with fluctuating prices based on countless factors like supply and demand dynamics, input costs, seasonality, and consumer preferences. Accurately accounting for all these variables to set an artificial price is a daunting, if not impossible, task. Setting prices too low can discourage production and lead to shortages, while setting them too high might not provide meaningful relief for consumers. The constantly evolving nature of markets further complicates this delicate balancing act.

Implementing and enforcing price controls inevitably creates an administrative burden on governments. Resources are required to monitor markets, identify violations, and penalize those who circumvent price ceilings. This enforcement can strain government budgets and divert resources from other essential services. Additionally, price controls often fuel the growth of black markets, where goods are traded illegally at prices above the mandated ceilings. This necessitates further enforcement efforts, creating a vicious regulation and illicit activity cycle.

Price controls can create significant uncertainty for investors providing goods and services. The prospect of government intervention in pricing can deter investment in essential sectors as investors seek stability and predictability. When price ceilings constrain profits, companies have less incentive to innovate or invest in research and development. This can hinder technological advancements and limit the availability of new and improved products.

What are the other policy options for price controls in Kenya?

While the Price Control Act of 2011 aims to ensure the affordability of essential goods, its reliance on setting maximum prices can lead to market distortions. Exploring alternative policy options might offer more sustainable and less disruptive solutions. One such alternative is targeted subsidies. Instead of blanket price controls that impact the entire market, targeted subsidies directed at low-income households could prove more efficient. This approach directly assists those in need, ensuring affordability without unintended consequences for others. Targeted subsidies maintain market efficiency by allowing prices to fluctuate based on supply and demand, incentivizing production, and discouraging shortages. Additionally, this method can be more cost-effective than broad price controls, as government expenditure is focused on vulnerable populations.

Another alternative is promoting competition within essential goods sectors. Fostering a competitive landscape can naturally moderate prices and give consumers more choices. A competitive market incentivizes businesses to offer competitive prices to attract customers, indirectly achieving the Act’s goal of reasonable prices. This market-driven solution relies on natural forces to regulate prices, reducing the need for artificial controls. Moreover, competition encourages businesses to innovate, improve efficiency, and offer better quality goods and services, ultimately benefiting consumers with more excellent choices and bargaining power.

Instead of treating the symptom (high prices) with price controls, focus on the root causes of supply-side constraints and offer a more sustainable solution. Prices can stabilize naturally by boosting supply and addressing bottlenecks, increasing availability and affordability in the long run. This approach addresses the reasons for high prices, leading to more lasting solutions. Furthermore, investing in infrastructure, logistics, or technology to improve supply chains can positively impact economic growth.

End Notes

[1] Neely, Christopher. “Why Price Controls Should Stay in the History Books.” Www.stlouisfed.org, 24 Mar. 2022, www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/2022/mar/why-price-controls-should-stay-history-books.

[2] Andae, Gerald. “Supermarkets Ration Sh100 Maize Flour Purchases on Buying Stampede.” Business Daily, Business Daily, 21 July 2022, www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/markets/commodities/supermarkets-ration-sh100-maize-flour-purchases-3887744

[3] Guénette, Justin-Damien. Price Controls Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes. 2020, documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/735161586781898890/pdf/Price-Controls-Good-Intentions-Bad-Outcomes.pdf.

[4] Fengler, Wolfgang. “How Price Controls Can Lead to Higher Prices.” World Bank Blogs, 2024, blogs.worldbank.org/en/africacan/how-price-controls-can-lead-to-higher-prices.

[5] Bloomenthal, Andrew. “Asymmetric Information in Economics Explained.” Investopedia, 19 Jan. 2021, www.investopedia.com/terms/a/asymmetricinformation.asp.

More Blogs

Gen Z Collective Action on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Introduction The Finance Bill 2024 in Kenya sparked a wave of collective action primarily driven by Gen Z, marking a significant moment for youth engagement in Kenyan politics. This younger generation, known for their digital fluency and facing bleak economic prospects, utilised social media platforms to voice their discontent and mobilise protests against the proposed […]

Two Immediate Monetary-Framework Imperatives for Mr. Mbadi

The credibility of Monetary Policy in Kenya is compromised at present by two factors: As we anticipated mid-year, inflation is headed below the target range for the first time; The 7-member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has four vacancies. In light of the former prospect, the MPC reduced the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) Policy Rate, […]

Important dates and Citizen Concerns During Budget Planning Phase for Fiscal Year 2025/2026

The Budget formulation and preparation process in Kenya is guided by a budget calendar which indicates the timelines for key activities issued in accordance with Section 36 of the Public Finance Management Act, 2012.These provide guidelines on the procedures for preparing the subsequent financial year and the Medium-Term budget forecasts. The Launch of the budget […]

Adjusted IMF Program Demands on Kenya

In the IMF WEO published yesterday, the IMF elaborated its macroeconomic framework for the ongoing IMF program. The numbers clarify how the program, derailed by the mid-year Gen-Z protests, has been adjusted to make possible the Board meeting for the combined 7th and 8th Reviews scheduled for October 30. The adjustments, unfortunately, again raise profound […]

What does the Nobel Prize in Economics 2024 mean for Constitution Implementation in Kenya?

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for their research on how a country’s institutions significantly impact its long-term economic success.[1] Their work emphasizes that it’s not just about a nation’s resources or technological advancements but rather the “rules of the game” that truly matter. Countries with […]