Adjusted IMF Program Demands on Kenya

Category: Monetary Policy

By: Kwame Owino, Maureen Barasa, Peter Doyle,

In the IMF WEO published yesterday, the IMF elaborated its macroeconomic framework for the ongoing IMF program.

The numbers clarify how the program, derailed by the mid-year Gen-Z protests, has been adjusted to make possible the Board meeting for the combined 7th and 8th Reviews scheduled for October 30.

The adjustments, unfortunately, again raise profound questions about the quality of the IMF’s technical work on Kenya, with implications for both for the immediate and long-term outlook.

The following table summarizes the Spring WEO in the top panel (green), the latest Fall WEO numbers in the mid panel (red), and the difference between the two in the lower panel (yellow).

Table 1: Spring and Fall 2024 WEOs

Trend Real GDP Growth

As so much is so evidently wrong with these new IMF numbers, we open by welcoming the single clear major improvement in the Fall WEO numbers compared to earlier staff projections.

Following our assessment issued mid-year (And then, Floods), the IMF have finally revised down their estimate of Kenya’s long run growth fate from 5.3 to 5.0 percent (See the top row of the mid- and lower-panels. This reflects that outturns have systematically fallen well short of their earlier projections and heralds a more realistic assessment of Kenya’s debt-carrying capacity.

That said, the new number, though more realistic, remains well below Kenya’s growth potential. The gap reflects that the IMF program still fails to correct any of the key “antecedents” or conjunctural policy misspecifications which are constraining Kenya’s short- and long-run growth.

Inflation

However, in those circumstances, what is gained in terms of “realism” in assessing Kenya’s debt carrying capacity from the downward revision in trend real GDP growth is largely undone in “unrealism” in the IMF inflation projections, starting in 2024/25.

The Fall WEO just published projects end-2024 12-month CPI to be 4.5 percent. However, the 12-month rate for September had already fallen to 3.6 percent.

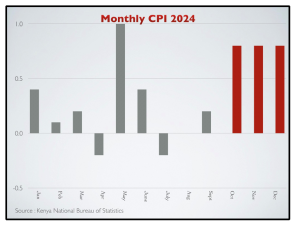

As a matter of pure algebra, in order for the end December 12 month rate to rise back up to the IMF-projected 4.5 percent for December, the monthly headline inflation rates for October December 2024 have to be of the order of magnitude displayed in the following chart in the red bars.

Chart 1:Monthly Change in the CPI

There is nothing in the macroeconomic conjuncture, transmitting into food or non-food prices, to justify a forecast of monthly inflation in the last three months of 2024 of that order of magnitude, so far out of line with the trend established throughout 2024 so far (grey bars).

Instead, as we warned in July and August to the surprise of many commentators then, on IMF program mandated policies and absent any major new shocks, the 12-month rate of inflation is set to fall below the Central Bank of Kenya Inflation Target Band of 5 percent +/- 2½ percent around the turn of the year.

This increasingly evident prospect given data outturns since then have in the past week even been recognized by the President. Rather than face having to acknowledge this imminent target undershoot as a serious failure of policy, he has effectively distanced himself from the current Inflation Target Band by declaring that he is now “targeting sub 3 percent inflation in 2025”.

But the IMF staff still do not see this. Their difficulties in projecting 12-month inflation just three months ahead continue in their projections for 2025 as a whole.

In most countries without IMF programs and with inflation-targeting central banks. IMF staff simply project year-ahead-and-beyond inflation to conform with the Central Bank targets on the assumption that the monetary authorities are competent and committed to “doing whatever it takes” to deliver their targets. That is evidently what underpins the IMF Staff inflation projections for Kenya for 2025.

But Kenya has a program. So, the Central Bank of Kenya is constrained by the conditionality in that program. So, IMF staff cannot assume that the monetary authorities know what to do to deliver their inflation target and intend to do it because, in such cases, the monetary authorities will do as the IMF instruct, right or wrong. The judgement on which the IMF forecast depends therefore is not that of the monetary authorities but is that of the IMF staff itself.

And as is all too evident even just from the 2024 end December IMF projections, the IMF Kenya team have considerable difficulties projecting inflation coherently under their own program policy framework.

With 12-month inflation actually set to fall to 2½ percent or lower around the turn of the year (contra the IMF projections), the IMF Fall WEO just published forecasts it to rise back up to 5.3 percent by December 2025 (red panel in the table). IMF staff forecast this sharp resurgence in inflation despite a further 0.8 percentage point of GDP fiscal tightening required by the IMF in calendar 2025 and real interest rates—the Central Bank of Kenya policy rate of 12 percent less trend monthly non-food inflation through 2024 of some 1½ percent—of the order of 10½ percent.

With those policy settings, it is unclear what macroeconomic factors the IMF Staff are assuming will drive underlying inflation back up in 2025, as they project, absent an immediate reduction from 12 to 9 percent or less in the Central Bank of Kenya policy rate. Given the inflation outlook, we called for a cut of that magnitude to take place in mid 2024. But IMF staff continue to reject our counsel.

The prospect of an inflation undershoot has potentially significant implications for the budget outlook, both for 2024/25 and for calendar 2025, as discussed below.

Primary Balance Targets

Following the Gen-Z protests and the associated abandonment of the 2024/25 Finance Act, the IMF have rephased the program fiscal parameters for 2024 and 2025, and beyond.

In particular, they have lowered the primary surplus targets for 2024 and 2025 by 0.8 and 0.5 percentage points of GDP (yellow panel in the table), while raising the primary surplus targets for 2027-2028. On these IMF primary balance numbers, budget pain has been postponed to Kenya’s election eve.

In that context, the IMF revenue outlook has also been revised, but only modestly. The sharp 1½ percentage point of GDP rise in revenue ratios from 2023 to 2025 that the IMF had demanded in Spring 2024 (green panel in the table)—which underlay the 2024/25 Finance Bill and the associated Gen-Z protests—has been lowered a little, to 1.3 percentage points of GDP now (red panel in the table).

So not only is budget pain in terms of the primary balance adjustment delayed to election eve, but in addition, these numbers suggest that IMF staff are demanding now that almost all of the tax rises that were included in the abandoned 2024 Finance Bill must return, in one form or another, in 2025. Those are necessary, on these IMF numbers, to accommodate increases in public spending ratios for 2026-28 relative to the Spring projections.

The political feasibility of this is unclear to us. The Government has the votes in Parliament to force through tax rises following the post Gen-Z political realignments. But it evidently had those votes in mid 2024 also and yet was forced to retreat. And, in this context, anticipation of additional primary balance adjustment on election eve seems highly optimistic.

This is also why the inflation projection for 2025 matters. If, as we anticipate on IMF staff approved monetary policy settings, average inflation in 2025 will be as much as one percentage point lower than staff projections, so nominal revenue will be lower correspondingly than staff project, even as nominal expenditure rises as budgeted. This heralds further rounds of fiscal adjustment demanded by staff as nominal revenue shortfalls continue for the rest of this calendar year into next in order to meet its latest set of primary surplus targets relative to GDP.

In any event, there also seems to have been a substantial reduction in the overall level of revenues to GDP. IMF staff showed these at 18 percent of GDP for 2023 in the Spring vintage (red panel in the table); they now show them at 16.9 percent of GDP in 2023 (green panel in the table) with an insignificant adjustment in nominal GDP for 2023 (yellow panel in the table).

It is unclear what underlies this 1 percentage point of GDP adjustment in the level of revenues in the entire framework.

Debt Ratios

We are also puzzled by the debt ratio now projected by IMF staff of 69.9 percent of GDP for December 2024 (red panel in the table).

That ratio compares with 73 percent of GDP projected by IMF staff in the Spring WEO (green panel in the table).

It is unclear why this ratio has dropped by 3.1 percentage points of GDP (yellow panel in the table) when there is little adjustment in the debt ratio in the base (2023), a 2 percent drop in projected nominal GDP, and bigger primary and overall deficits.

Is there some 3-percentage point of GDP in privatization receipts which was not anticipated in the Spring Staff forecasts for 2024, or is there an issue with the consistency of staff flow and stock projections?

Given these doubts, we are not confident that the debt projections shown by IMF Staff for later years maintain the necessary consistency between the flow and stock projections.

Debt Targets

That doubt about internal consistency acknowledged, on the staff projections, it is notable that in contrast to the Spring vintage of IMF Staff projections when debt ratios were shown falling to 63.4 percent of GDP in 2028 (green panel in the table), they are now shown falling only to 68 percent of GDP in 2028 now.

Since the entire program has been motivated by reducing these ratios, and the tumult in mid 2024 in Kenya was catalysed by the IMF insistence then that reducing these ratios to 63.4 percent of GDP was “unavoidably necessary”, it is unclear to us why the IMF judgement has changed so dramatically, so that now such reductions, in their view, are not necessary after all.

It begs the question: if those reductions are not necessary, why did the IMF put Kenya through such turmoil in mid-year—bringing the government to the brink of collapse, with well over 50 protesters dead—if those debt reductions are and therefore were not necessary?

Conclusion

The IMF Board discussion scheduled for October 30 will proceed on the basis of these staff numbers. Given that they are so doubtful—in terms of the realism of the inflation projections, the tolerance of the political fabric to sustain the reintroduction of the abandoned tax rises and then the further adjustments on election eve, and in terms of consistency between the flow and stock projections for the fiscal—we would, in the first instance, expect considerable challenge to them at the IMF Board meeting. That is particularly so as two reviews have been combined so the anticipated disbursement predicated on these numbers is substantial.

More substantively for Kenya itself, however, we remain deeply concerned that the calibre of analysis underpinning the macroeconomic boundaries the IMF is setting for Kenya continues to fall short of the highest professional standards, with severe implications for Kenya’s prospects.

And all of these concerns are amplified because everything remains subject to the pending ruling on the constitutionality of the 2023/24 Finance Act. If the challenge is approved, all tax policy settings might have to revert to those of 2022/23, substantially undermining revenue and rendering large tax refunds due. We see no signs in these new IMF numbers that the macroeconomic framework is a robust as necessary to face that imminent contingency.

More Blogs

Important dates and Citizen Concerns During Budget Planning Phase for Fiscal Year 2025/2026

The Budget formulation and preparation process in Kenya is guided by a budget calendar which indicates the timelines for key activities issued in accordance with Section 36 of the Public Finance Management Act, 2012.These provide guidelines on the procedures for preparing the subsequent financial year and the Medium-Term budget forecasts. The Launch of the budget […]

What does the Nobel Prize in Economics 2024 mean for Constitution Implementation in Kenya?

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for their research on how a country’s institutions significantly impact its long-term economic success.[1] Their work emphasizes that it’s not just about a nation’s resources or technological advancements but rather the “rules of the game” that truly matter. Countries with […]

Highlights of The World Trade Report 2024.

The World Trade Report 2024 was launched at the start of the WTO Public Forum 2024 in Geneva titled “Trade and Inclusiveness: How to Make Trade Work for All”[1], and this blog will seek to highlight some of the most profound insights. The report delves into the crucial relationship between international trade and inclusive economic […]

The Grounds to Repeal the Price Control Act of 2011

The Price Control Act of 2011, with its imposition of price ceilings on essential goods, represents a significant intervention in the natural forces of supply and demand that govern a free market. The Act empowers the Minister to control the prices of essential goods, preventing them from becoming unaffordable. The Act outlines a specific mechanism […]

Why is Kenya’s Fiscal Consolidation Agenda Facing Failure?

The earliest proposition of fiscal consolidation can be traced back to the Keynesian theory which argues that fiscal austerity measures reduce growth and increases unemployment through aggregate demand effects. According to this theory, government undertaking contractionary fiscal policies of either reducing government spending or increasing tax rates, will eventually suffer a reduction in aggregate demand […]

Adjusted IMF Program Demands on Kenya

| Post date: Wed, Oct 23, 2024 |

| Category: Monetary Policy |

| By: Kwame Owino, Maureen Barasa, Peter Doyle, |

In the IMF WEO published yesterday, the IMF elaborated its macroeconomic framework for the ongoing IMF program.

The numbers clarify how the program, derailed by the mid-year Gen-Z protests, has been adjusted to make possible the Board meeting for the combined 7th and 8th Reviews scheduled for October 30.

The adjustments, unfortunately, again raise profound questions about the quality of the IMF’s technical work on Kenya, with implications for both for the immediate and long-term outlook.

The following table summarizes the Spring WEO in the top panel (green), the latest Fall WEO numbers in the mid panel (red), and the difference between the two in the lower panel (yellow).

Table 1: Spring and Fall 2024 WEOs

Trend Real GDP Growth

As so much is so evidently wrong with these new IMF numbers, we open by welcoming the single clear major improvement in the Fall WEO numbers compared to earlier staff projections.

Following our assessment issued mid-year (And then, Floods), the IMF have finally revised down their estimate of Kenya’s long run growth fate from 5.3 to 5.0 percent (See the top row of the mid- and lower-panels. This reflects that outturns have systematically fallen well short of their earlier projections and heralds a more realistic assessment of Kenya’s debt-carrying capacity.

That said, the new number, though more realistic, remains well below Kenya’s growth potential. The gap reflects that the IMF program still fails to correct any of the key “antecedents” or conjunctural policy misspecifications which are constraining Kenya’s short- and long-run growth.

Inflation

However, in those circumstances, what is gained in terms of “realism” in assessing Kenya’s debt carrying capacity from the downward revision in trend real GDP growth is largely undone in “unrealism” in the IMF inflation projections, starting in 2024/25.

The Fall WEO just published projects end-2024 12-month CPI to be 4.5 percent. However, the 12-month rate for September had already fallen to 3.6 percent.

As a matter of pure algebra, in order for the end December 12 month rate to rise back up to the IMF-projected 4.5 percent for December, the monthly headline inflation rates for October December 2024 have to be of the order of magnitude displayed in the following chart in the red bars.

Chart 1:Monthly Change in the CPI

There is nothing in the macroeconomic conjuncture, transmitting into food or non-food prices, to justify a forecast of monthly inflation in the last three months of 2024 of that order of magnitude, so far out of line with the trend established throughout 2024 so far (grey bars).

Instead, as we warned in July and August to the surprise of many commentators then, on IMF program mandated policies and absent any major new shocks, the 12-month rate of inflation is set to fall below the Central Bank of Kenya Inflation Target Band of 5 percent +/- 2½ percent around the turn of the year.

This increasingly evident prospect given data outturns since then have in the past week even been recognized by the President. Rather than face having to acknowledge this imminent target undershoot as a serious failure of policy, he has effectively distanced himself from the current Inflation Target Band by declaring that he is now “targeting sub 3 percent inflation in 2025”.

But the IMF staff still do not see this. Their difficulties in projecting 12-month inflation just three months ahead continue in their projections for 2025 as a whole.

In most countries without IMF programs and with inflation-targeting central banks. IMF staff simply project year-ahead-and-beyond inflation to conform with the Central Bank targets on the assumption that the monetary authorities are competent and committed to “doing whatever it takes” to deliver their targets. That is evidently what underpins the IMF Staff inflation projections for Kenya for 2025.

But Kenya has a program. So, the Central Bank of Kenya is constrained by the conditionality in that program. So, IMF staff cannot assume that the monetary authorities know what to do to deliver their inflation target and intend to do it because, in such cases, the monetary authorities will do as the IMF instruct, right or wrong. The judgement on which the IMF forecast depends therefore is not that of the monetary authorities but is that of the IMF staff itself.

And as is all too evident even just from the 2024 end December IMF projections, the IMF Kenya team have considerable difficulties projecting inflation coherently under their own program policy framework.

With 12-month inflation actually set to fall to 2½ percent or lower around the turn of the year (contra the IMF projections), the IMF Fall WEO just published forecasts it to rise back up to 5.3 percent by December 2025 (red panel in the table). IMF staff forecast this sharp resurgence in inflation despite a further 0.8 percentage point of GDP fiscal tightening required by the IMF in calendar 2025 and real interest rates—the Central Bank of Kenya policy rate of 12 percent less trend monthly non-food inflation through 2024 of some 1½ percent—of the order of 10½ percent.

With those policy settings, it is unclear what macroeconomic factors the IMF Staff are assuming will drive underlying inflation back up in 2025, as they project, absent an immediate reduction from 12 to 9 percent or less in the Central Bank of Kenya policy rate. Given the inflation outlook, we called for a cut of that magnitude to take place in mid 2024. But IMF staff continue to reject our counsel.

The prospect of an inflation undershoot has potentially significant implications for the budget outlook, both for 2024/25 and for calendar 2025, as discussed below.

Primary Balance Targets

Following the Gen-Z protests and the associated abandonment of the 2024/25 Finance Act, the IMF have rephased the program fiscal parameters for 2024 and 2025, and beyond.

In particular, they have lowered the primary surplus targets for 2024 and 2025 by 0.8 and 0.5 percentage points of GDP (yellow panel in the table), while raising the primary surplus targets for 2027-2028. On these IMF primary balance numbers, budget pain has been postponed to Kenya’s election eve.

In that context, the IMF revenue outlook has also been revised, but only modestly. The sharp 1½ percentage point of GDP rise in revenue ratios from 2023 to 2025 that the IMF had demanded in Spring 2024 (green panel in the table)—which underlay the 2024/25 Finance Bill and the associated Gen-Z protests—has been lowered a little, to 1.3 percentage points of GDP now (red panel in the table).

So not only is budget pain in terms of the primary balance adjustment delayed to election eve, but in addition, these numbers suggest that IMF staff are demanding now that almost all of the tax rises that were included in the abandoned 2024 Finance Bill must return, in one form or another, in 2025. Those are necessary, on these IMF numbers, to accommodate increases in public spending ratios for 2026-28 relative to the Spring projections.

The political feasibility of this is unclear to us. The Government has the votes in Parliament to force through tax rises following the post Gen-Z political realignments. But it evidently had those votes in mid 2024 also and yet was forced to retreat. And, in this context, anticipation of additional primary balance adjustment on election eve seems highly optimistic.

This is also why the inflation projection for 2025 matters. If, as we anticipate on IMF staff approved monetary policy settings, average inflation in 2025 will be as much as one percentage point lower than staff projections, so nominal revenue will be lower correspondingly than staff project, even as nominal expenditure rises as budgeted. This heralds further rounds of fiscal adjustment demanded by staff as nominal revenue shortfalls continue for the rest of this calendar year into next in order to meet its latest set of primary surplus targets relative to GDP.

In any event, there also seems to have been a substantial reduction in the overall level of revenues to GDP. IMF staff showed these at 18 percent of GDP for 2023 in the Spring vintage (red panel in the table); they now show them at 16.9 percent of GDP in 2023 (green panel in the table) with an insignificant adjustment in nominal GDP for 2023 (yellow panel in the table).

It is unclear what underlies this 1 percentage point of GDP adjustment in the level of revenues in the entire framework.

Debt Ratios

We are also puzzled by the debt ratio now projected by IMF staff of 69.9 percent of GDP for December 2024 (red panel in the table).

That ratio compares with 73 percent of GDP projected by IMF staff in the Spring WEO (green panel in the table).

It is unclear why this ratio has dropped by 3.1 percentage points of GDP (yellow panel in the table) when there is little adjustment in the debt ratio in the base (2023), a 2 percent drop in projected nominal GDP, and bigger primary and overall deficits.

Is there some 3-percentage point of GDP in privatization receipts which was not anticipated in the Spring Staff forecasts for 2024, or is there an issue with the consistency of staff flow and stock projections?

Given these doubts, we are not confident that the debt projections shown by IMF Staff for later years maintain the necessary consistency between the flow and stock projections.

Debt Targets

That doubt about internal consistency acknowledged, on the staff projections, it is notable that in contrast to the Spring vintage of IMF Staff projections when debt ratios were shown falling to 63.4 percent of GDP in 2028 (green panel in the table), they are now shown falling only to 68 percent of GDP in 2028 now.

Since the entire program has been motivated by reducing these ratios, and the tumult in mid 2024 in Kenya was catalysed by the IMF insistence then that reducing these ratios to 63.4 percent of GDP was “unavoidably necessary”, it is unclear to us why the IMF judgement has changed so dramatically, so that now such reductions, in their view, are not necessary after all.

It begs the question: if those reductions are not necessary, why did the IMF put Kenya through such turmoil in mid-year—bringing the government to the brink of collapse, with well over 50 protesters dead—if those debt reductions are and therefore were not necessary?

Conclusion

The IMF Board discussion scheduled for October 30 will proceed on the basis of these staff numbers. Given that they are so doubtful—in terms of the realism of the inflation projections, the tolerance of the political fabric to sustain the reintroduction of the abandoned tax rises and then the further adjustments on election eve, and in terms of consistency between the flow and stock projections for the fiscal—we would, in the first instance, expect considerable challenge to them at the IMF Board meeting. That is particularly so as two reviews have been combined so the anticipated disbursement predicated on these numbers is substantial.

More substantively for Kenya itself, however, we remain deeply concerned that the calibre of analysis underpinning the macroeconomic boundaries the IMF is setting for Kenya continues to fall short of the highest professional standards, with severe implications for Kenya’s prospects.

And all of these concerns are amplified because everything remains subject to the pending ruling on the constitutionality of the 2023/24 Finance Act. If the challenge is approved, all tax policy settings might have to revert to those of 2022/23, substantially undermining revenue and rendering large tax refunds due. We see no signs in these new IMF numbers that the macroeconomic framework is a robust as necessary to face that imminent contingency.

More Blogs

Important dates and Citizen Concerns During Budget Planning Phase for Fiscal Year 2025/2026

The Budget formulation and preparation process in Kenya is guided by a budget calendar which indicates the timelines for key activities issued in accordance with Section 36 of the Public Finance Management Act, 2012.These provide guidelines on the procedures for preparing the subsequent financial year and the Medium-Term budget forecasts. The Launch of the budget […]

What does the Nobel Prize in Economics 2024 mean for Constitution Implementation in Kenya?

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for their research on how a country’s institutions significantly impact its long-term economic success.[1] Their work emphasizes that it’s not just about a nation’s resources or technological advancements but rather the “rules of the game” that truly matter. Countries with […]

Highlights of The World Trade Report 2024.

The World Trade Report 2024 was launched at the start of the WTO Public Forum 2024 in Geneva titled “Trade and Inclusiveness: How to Make Trade Work for All”[1], and this blog will seek to highlight some of the most profound insights. The report delves into the crucial relationship between international trade and inclusive economic […]

The Grounds to Repeal the Price Control Act of 2011

The Price Control Act of 2011, with its imposition of price ceilings on essential goods, represents a significant intervention in the natural forces of supply and demand that govern a free market. The Act empowers the Minister to control the prices of essential goods, preventing them from becoming unaffordable. The Act outlines a specific mechanism […]

Why is Kenya’s Fiscal Consolidation Agenda Facing Failure?

The earliest proposition of fiscal consolidation can be traced back to the Keynesian theory which argues that fiscal austerity measures reduce growth and increases unemployment through aggregate demand effects. According to this theory, government undertaking contractionary fiscal policies of either reducing government spending or increasing tax rates, will eventually suffer a reduction in aggregate demand […]