Two Immediate Monetary-Framework Imperatives for Mr. Mbadi

Category: Monetary-Framework

By: Kwame Owino, Maureen Barasa, Peter Doyle,

The credibility of Monetary Policy in Kenya is compromised at present by two factors:

- As we anticipated mid-year, inflation is headed below the target range for the first time;

- The 7-member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has four vacancies.

In light of the former prospect, the MPC reduced the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) Policy Rate, first by 25 bps in August and then by 75 bps in October, following global central banks.

These steps significantly lagged our counsel in July that the CBK should cut its rate by 300 bps immediately.

As a result of that lag, one-month annualized non-food inflation has been running at an annualized rate of just 1.4 percent between February and October, culminating in the 12-month rate in the headline CPI in October of 2.7 percent, barely inside the target band, and still falling.

That has been but one issue in the incoherent and thus much-troubled IMF program, which has limped on recently with two reviews combined amid a raft of questions about the integrity of the adjustments under which that continuation was arranged.

In that broad context, the President, appraised of the imminent fall of 12-month inflation below three percent recently declared that “sub 3-percent” inflation as his goal for 2025.

In doing so, he has preferred to move the goalposts rather than concede that inflation below the target band is a major failure of policy.

His repositioning has however brought into question whether the long-standing target framework—of 5 percent with a band of 2½ percentage points either side—has been or will be replaced. And the possibility that it has been has been given immediate relevance as a majority of the chairs on the MPC are due for appointment.

So two immediate monetary framework imperatives arise for Mr. Mbadi:

- Should the 5 percent target band be abandoned for something formally expressing “sub 3 percent”, and if so, what exactly?

- And on what basis should he appoint the new MPC members? We address these issues in

1. Inflation Target Number

Much is unclear about the President’s statement—which is the problem.

Does he intend that the 5 +/- 2½ percent band should remain, but prefer or predict that inflation should be between 3 and 2½ percent for 2025, or for parts thereof, or would he be happy with inflation below—and possibly well below—2½ percent for 2025, or parts thereof, or permanently?

These issues are neither academic nor “just politics”. At a time of considerable fiscal uncertainty, multiple shortcomings in the design of the IMF program, and heightened domestic and global economic strains, the sudden change of monetary framework in the context of below-target band inflation is in grave danger of being seen in markets as impulsive, if not chaotic, not least because it is so vague.

In averting that risk, the global evidence is clear: there is no good case for Kenya to lower its inflation target now to those typical of the global metropole (See Figure 1).

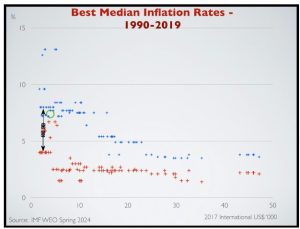

Figure 1. Median Inflation Rates of the Fastest Growing real GDP/capita Countries, 1990-2019

To see this, in Figure 1, we report the inflation performance of the countries which achieved the fastest growth of GDP per capita over three decades after 1990. We report the range of the median inflation rates for such countries at each level of GDP per capita. We do this by constructing panels of 8 such best-growth countries at each level of GDP per capita and reporting the interquartile range of each panel’s median inflation rates.

Thus, the blue dots show the upper end of the interquartile range of median inflation rates of the fast-per-capita growth countries worldwide. The red dots show the lower end of that range.

That evidence shows that optimal inflation falls with GDP per capita, falling to 1-3 percent for the highest income cases in the global metropole. But, critically, it also shows a best-practice range of 4-8 percent for countries around Kenya’s real GDP per capita (See arrows in Figure 1).

Countries in Kenya’s GDP per capita neighborhood with inflation systematically below that range fall short of best peer growth, generally significantly. Such countries include those in the CFA franc zone. These have long secured metropole rates of inflation of around 2 percent alongside rates of per capita income growth that at best matches the metropole, i.e., has been well below best peer potential at CFA zone levels of GDP per capita.

We contend that best inflation practice is in the 4-8 percent range for low income countries— rather the 2 percent typical of the global metropole—primarily because lower income countries have difficulty raising revenue, and such moderate inflation raises necessary revenue via seignorage. That revenue is one of the sources of their superior trend growth performance.

This evidence puts into context the common claim that “inflation hurts the poorest most”. That claim may be true of unanticipated hyperinflation. But the poorest are the prime beneficiaries of best peer per capita growth which inflation in the 4-8 percent range helps to bring about.

Kenya’s median inflation in 1990-2019 was around 7 percent, within the range (See green circle in Figure 1). So, there is no evidence from this that Kenya’s long-standing per capita growth shortfalls relative to best peers is systematically attributable to errant monetary policy.

And while Kenya’s inflation target of 5 percent is also within the range, it is toward the lower end. So rather than needing to be reduced, if anything Kenya’s inflation target may even be a little on the low side.

That range has the compelling merit of reflecting the best performing countries globally over thirty years in Kenya’s circumstances. So, in any choice between mimicking the global metropole now—an opportunistic disinflation to “lock in” the effects of recent policy errors—versus following best practice for “countries like us”, we unreservedly advocate the latter. Otherwise, Kenya would further compromise its per capita growth by aggravating the revenue problems it, all to evidently, already has.

Indeed, this global evidence suggests that Kenya’s income per capita would have to roughly double before there is any case to lower the inflation target below 5 percent and roughly quintuple before that case becomes overwhelming. Sadly, these prospects are remote.

Furthermore, the case against lowering the inflation target does not just concern long-run best practice and long run revenue, but also the revenue outlook specifically for 2024/25.

The revenue estimates underlying the government’s budget and revised IMF program target for a primary surplus of 1.3 percent of GDP assume that inflation will be on target, at 5 percent. If

—as is already occurring—12-month inflation falls well short of that and remains subdued, the annual average inflation outturn relevant for the 2024/25 revenue estimates could fall short of the budget estimates in 2024/25.

Those shortfalls would be compounded by the hit to real output relative to budget projections arising from the over-tight monetary policy yielding that inflation outturn. Both factors will compound the over-projection of real GDP and nominal revenue which has disfigured the entire IMF program because its conditionality has been systematically mis specified.

These risks are all underlined by the marked deceleration in quarterly seasonally adjusted nominal GDP recorded to Q2 2024 from Q3 2023 and in real GDP since Q4 2023, as well as in shortfalls in monthly revenue relative to budget estimates already recorded in 2024/25.

So sub 3 percent inflation may force a supplementary budget for 2024/25 to apply yet further rounds of spending cuts if the target of a primary surplus of 1.3 percent of GDP is to be secured, as both the authorities and the IMF—against our counsel—insist.

Accordingly, we see no case to meddle at this late stage with one of the relatively few major framing elements of the IMF program which, in our view, was correct—namely the monetary policy framework.

In any event, it does not help that at the same time as the President intimated a new sub-three percent target, implying interest rates higher for longer, the CS Treasury at his recent 50-day anniversary press event sent the opposite message that interest rates “should” come down soon.

Instead, the imperatives are that both, along with the IMF, should unambiguously reaffirm the 5

+/- 2½ percent monetary policy target numbers, that both should avoid any statements about where interest rates and inflation will or should go beyond that, and that the MPC should implement a further cut in the CBK rate of at least 200 bps immediately in order to get underlying inflation back up to target.

Accordingly, our monetary counsel remains as it has been since mid-year: don’t “fix” the framework; fix the policy.

2. MPC Appointments

That said, a major gap in the framework has to be filled. Following the expiry of non-renewable terms, the seven member MPC is now functioning with only three members, the minimum for quorum.

In the complex current macroeconomic environment, the MPC should be at full strength.

That probably should include appointing one or more non-nationals to the body to bring in outside expertise, perhaps via reciprocal arrangements with other African countries.

And it should definitely include an arrangement to ensure that the terms of MPC members are staggered—to avoid the present impasse whereby a majority of the MPC has to be appointed all at once.

But speed of appointments must not compromise quality. To avoid appointees who learn on the job at Kenya’s expense, or worse, who simply free-ride on the committee, Mr. Mbadi should apply high rigor in evaluating the merits of candidates.

To assist him in doing so, we suggest that he evaluate candidates on the basis of their answers to at least some of the following questions, every one of which—and more—they will have to tackle in detail once appointed:

- Are nominal wages and money leading or lagging indicators of inflation, or neither, in Kenya?

- If after all technical preparations and discussions, the MPC’s judgement on monetary policy contradicts IMF conditionality during a program, should the MPC apply its view or the IMF’s?

- Should the MPC, at each of its meetings, publish its “dot plot”?

- How should communication of the rationale for MPC decisions improve?

- Would MPC member policy disagreements in public undermine credibility or boost transparency?

- Should individual MPC members’ votes be published, including so that individual members can be accountable to Parliament for their voting records?

- Do inflation undershoots of the target band matter as much as inflation overshoots of the target band?

- Is Kenya’s target band too wide?

- If there is little response of commercial interest rates to the CBK rate, should that rate be adjusted more or is there something wrong with the monetary policy transmission mechanism, or both or neither?

- In setting the CBK rate to hit the inflation target, is it the direction of travel, or the level, or the differential with major central banks’ policy rates which matters?

- How should the monetary framework and policy respond to a large enduring but not permanent relative price shock?

- Should the MPC aim to stabilize the exchange rate? At what level? Using what instruments?

- Is the 40 percent appreciation of the real effective exchange rate of the Shilling since 2010 good or bad?

- Should the Shilling float?

- Is the level of Kenya’s International Reserves the MPC’s problem, or just the inflation target?

- How should monetary policy reflect concerns with financial sector fragility, in normal times, and in times of financial sector stress?

- How would consolidation of Kenya’s small banks affect competition and inclusion, and thus the transmission mechanism of monetary policy?

- Should MPC decisions take account of their impact on the budget?

- Should the MPC believe the government’s adopted budget when setting monetary policy?

- Is there a case for Open Market Operations or Quantitive Easing when the Central Bank of Kenya policy rate is above its effective floor?

- Is the central target for inflation in Kenya 5 percent or sub three percent?

- Should the MPC formally express a view on what the “best” inflation target number or exchange rate regime is?

- Should Kenya abandon the Shilling either for a common East African or a Pan-African currency?

- When should fuel be included and in the measure of core inflation in Kenya and when should it be excluded?

More Blogs

Gen Z Collective Action on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Introduction The Finance Bill 2024 in Kenya sparked a wave of collective action primarily driven by Gen Z, marking a significant moment for youth engagement in Kenyan politics. This younger generation, known for their digital fluency and facing bleak economic prospects, utilised social media platforms to voice their discontent and mobilise protests against the proposed […]

Important dates and Citizen Concerns During Budget Planning Phase for Fiscal Year 2025/2026

The Budget formulation and preparation process in Kenya is guided by a budget calendar which indicates the timelines for key activities issued in accordance with Section 36 of the Public Finance Management Act, 2012.These provide guidelines on the procedures for preparing the subsequent financial year and the Medium-Term budget forecasts. The Launch of the budget […]

Adjusted IMF Program Demands on Kenya

In the IMF WEO published yesterday, the IMF elaborated its macroeconomic framework for the ongoing IMF program. The numbers clarify how the program, derailed by the mid-year Gen-Z protests, has been adjusted to make possible the Board meeting for the combined 7th and 8th Reviews scheduled for October 30. The adjustments, unfortunately, again raise profound […]

What does the Nobel Prize in Economics 2024 mean for Constitution Implementation in Kenya?

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for their research on how a country’s institutions significantly impact its long-term economic success.[1] Their work emphasizes that it’s not just about a nation’s resources or technological advancements but rather the “rules of the game” that truly matter. Countries with […]

Highlights of The World Trade Report 2024.

The World Trade Report 2024 was launched at the start of the WTO Public Forum 2024 in Geneva titled “Trade and Inclusiveness: How to Make Trade Work for All”[1], and this blog will seek to highlight some of the most profound insights. The report delves into the crucial relationship between international trade and inclusive economic […]

Two Immediate Monetary-Framework Imperatives for Mr. Mbadi

| Post date: Sun, Nov 3, 2024 |

| Category: Monetary-Framework |

| By: Kwame Owino, Maureen Barasa, Peter Doyle, |

The credibility of Monetary Policy in Kenya is compromised at present by two factors:

- As we anticipated mid-year, inflation is headed below the target range for the first time;

- The 7-member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has four vacancies.

In light of the former prospect, the MPC reduced the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) Policy Rate, first by 25 bps in August and then by 75 bps in October, following global central banks.

These steps significantly lagged our counsel in July that the CBK should cut its rate by 300 bps immediately.

As a result of that lag, one-month annualized non-food inflation has been running at an annualized rate of just 1.4 percent between February and October, culminating in the 12-month rate in the headline CPI in October of 2.7 percent, barely inside the target band, and still falling.

That has been but one issue in the incoherent and thus much-troubled IMF program, which has limped on recently with two reviews combined amid a raft of questions about the integrity of the adjustments under which that continuation was arranged.

In that broad context, the President, appraised of the imminent fall of 12-month inflation below three percent recently declared that “sub 3-percent” inflation as his goal for 2025.

In doing so, he has preferred to move the goalposts rather than concede that inflation below the target band is a major failure of policy.

His repositioning has however brought into question whether the long-standing target framework—of 5 percent with a band of 2½ percentage points either side—has been or will be replaced. And the possibility that it has been has been given immediate relevance as a majority of the chairs on the MPC are due for appointment.

So two immediate monetary framework imperatives arise for Mr. Mbadi:

- Should the 5 percent target band be abandoned for something formally expressing “sub 3 percent”, and if so, what exactly?

- And on what basis should he appoint the new MPC members? We address these issues in

1. Inflation Target Number

Much is unclear about the President’s statement—which is the problem.

Does he intend that the 5 +/- 2½ percent band should remain, but prefer or predict that inflation should be between 3 and 2½ percent for 2025, or for parts thereof, or would he be happy with inflation below—and possibly well below—2½ percent for 2025, or parts thereof, or permanently?

These issues are neither academic nor “just politics”. At a time of considerable fiscal uncertainty, multiple shortcomings in the design of the IMF program, and heightened domestic and global economic strains, the sudden change of monetary framework in the context of below-target band inflation is in grave danger of being seen in markets as impulsive, if not chaotic, not least because it is so vague.

In averting that risk, the global evidence is clear: there is no good case for Kenya to lower its inflation target now to those typical of the global metropole (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Median Inflation Rates of the Fastest Growing real GDP/capita Countries, 1990-2019

To see this, in Figure 1, we report the inflation performance of the countries which achieved the fastest growth of GDP per capita over three decades after 1990. We report the range of the median inflation rates for such countries at each level of GDP per capita. We do this by constructing panels of 8 such best-growth countries at each level of GDP per capita and reporting the interquartile range of each panel’s median inflation rates.

Thus, the blue dots show the upper end of the interquartile range of median inflation rates of the fast-per-capita growth countries worldwide. The red dots show the lower end of that range.

That evidence shows that optimal inflation falls with GDP per capita, falling to 1-3 percent for the highest income cases in the global metropole. But, critically, it also shows a best-practice range of 4-8 percent for countries around Kenya’s real GDP per capita (See arrows in Figure 1).

Countries in Kenya’s GDP per capita neighborhood with inflation systematically below that range fall short of best peer growth, generally significantly. Such countries include those in the CFA franc zone. These have long secured metropole rates of inflation of around 2 percent alongside rates of per capita income growth that at best matches the metropole, i.e., has been well below best peer potential at CFA zone levels of GDP per capita.

We contend that best inflation practice is in the 4-8 percent range for low income countries— rather the 2 percent typical of the global metropole—primarily because lower income countries have difficulty raising revenue, and such moderate inflation raises necessary revenue via seignorage. That revenue is one of the sources of their superior trend growth performance.

This evidence puts into context the common claim that “inflation hurts the poorest most”. That claim may be true of unanticipated hyperinflation. But the poorest are the prime beneficiaries of best peer per capita growth which inflation in the 4-8 percent range helps to bring about.

Kenya’s median inflation in 1990-2019 was around 7 percent, within the range (See green circle in Figure 1). So, there is no evidence from this that Kenya’s long-standing per capita growth shortfalls relative to best peers is systematically attributable to errant monetary policy.

And while Kenya’s inflation target of 5 percent is also within the range, it is toward the lower end. So rather than needing to be reduced, if anything Kenya’s inflation target may even be a little on the low side.

That range has the compelling merit of reflecting the best performing countries globally over thirty years in Kenya’s circumstances. So, in any choice between mimicking the global metropole now—an opportunistic disinflation to “lock in” the effects of recent policy errors—versus following best practice for “countries like us”, we unreservedly advocate the latter. Otherwise, Kenya would further compromise its per capita growth by aggravating the revenue problems it, all to evidently, already has.

Indeed, this global evidence suggests that Kenya’s income per capita would have to roughly double before there is any case to lower the inflation target below 5 percent and roughly quintuple before that case becomes overwhelming. Sadly, these prospects are remote.

Furthermore, the case against lowering the inflation target does not just concern long-run best practice and long run revenue, but also the revenue outlook specifically for 2024/25.

The revenue estimates underlying the government’s budget and revised IMF program target for a primary surplus of 1.3 percent of GDP assume that inflation will be on target, at 5 percent. If

—as is already occurring—12-month inflation falls well short of that and remains subdued, the annual average inflation outturn relevant for the 2024/25 revenue estimates could fall short of the budget estimates in 2024/25.

Those shortfalls would be compounded by the hit to real output relative to budget projections arising from the over-tight monetary policy yielding that inflation outturn. Both factors will compound the over-projection of real GDP and nominal revenue which has disfigured the entire IMF program because its conditionality has been systematically mis specified.

These risks are all underlined by the marked deceleration in quarterly seasonally adjusted nominal GDP recorded to Q2 2024 from Q3 2023 and in real GDP since Q4 2023, as well as in shortfalls in monthly revenue relative to budget estimates already recorded in 2024/25.

So sub 3 percent inflation may force a supplementary budget for 2024/25 to apply yet further rounds of spending cuts if the target of a primary surplus of 1.3 percent of GDP is to be secured, as both the authorities and the IMF—against our counsel—insist.

Accordingly, we see no case to meddle at this late stage with one of the relatively few major framing elements of the IMF program which, in our view, was correct—namely the monetary policy framework.

In any event, it does not help that at the same time as the President intimated a new sub-three percent target, implying interest rates higher for longer, the CS Treasury at his recent 50-day anniversary press event sent the opposite message that interest rates “should” come down soon.

Instead, the imperatives are that both, along with the IMF, should unambiguously reaffirm the 5

+/- 2½ percent monetary policy target numbers, that both should avoid any statements about where interest rates and inflation will or should go beyond that, and that the MPC should implement a further cut in the CBK rate of at least 200 bps immediately in order to get underlying inflation back up to target.

Accordingly, our monetary counsel remains as it has been since mid-year: don’t “fix” the framework; fix the policy.

2. MPC Appointments

That said, a major gap in the framework has to be filled. Following the expiry of non-renewable terms, the seven member MPC is now functioning with only three members, the minimum for quorum.

In the complex current macroeconomic environment, the MPC should be at full strength.

That probably should include appointing one or more non-nationals to the body to bring in outside expertise, perhaps via reciprocal arrangements with other African countries.

And it should definitely include an arrangement to ensure that the terms of MPC members are staggered—to avoid the present impasse whereby a majority of the MPC has to be appointed all at once.

But speed of appointments must not compromise quality. To avoid appointees who learn on the job at Kenya’s expense, or worse, who simply free-ride on the committee, Mr. Mbadi should apply high rigor in evaluating the merits of candidates.

To assist him in doing so, we suggest that he evaluate candidates on the basis of their answers to at least some of the following questions, every one of which—and more—they will have to tackle in detail once appointed:

- Are nominal wages and money leading or lagging indicators of inflation, or neither, in Kenya?

- If after all technical preparations and discussions, the MPC’s judgement on monetary policy contradicts IMF conditionality during a program, should the MPC apply its view or the IMF’s?

- Should the MPC, at each of its meetings, publish its “dot plot”?

- How should communication of the rationale for MPC decisions improve?

- Would MPC member policy disagreements in public undermine credibility or boost transparency?

- Should individual MPC members’ votes be published, including so that individual members can be accountable to Parliament for their voting records?

- Do inflation undershoots of the target band matter as much as inflation overshoots of the target band?

- Is Kenya’s target band too wide?

- If there is little response of commercial interest rates to the CBK rate, should that rate be adjusted more or is there something wrong with the monetary policy transmission mechanism, or both or neither?

- In setting the CBK rate to hit the inflation target, is it the direction of travel, or the level, or the differential with major central banks’ policy rates which matters?

- How should the monetary framework and policy respond to a large enduring but not permanent relative price shock?

- Should the MPC aim to stabilize the exchange rate? At what level? Using what instruments?

- Is the 40 percent appreciation of the real effective exchange rate of the Shilling since 2010 good or bad?

- Should the Shilling float?

- Is the level of Kenya’s International Reserves the MPC’s problem, or just the inflation target?

- How should monetary policy reflect concerns with financial sector fragility, in normal times, and in times of financial sector stress?

- How would consolidation of Kenya’s small banks affect competition and inclusion, and thus the transmission mechanism of monetary policy?

- Should MPC decisions take account of their impact on the budget?

- Should the MPC believe the government’s adopted budget when setting monetary policy?

- Is there a case for Open Market Operations or Quantitive Easing when the Central Bank of Kenya policy rate is above its effective floor?

- Is the central target for inflation in Kenya 5 percent or sub three percent?

- Should the MPC formally express a view on what the “best” inflation target number or exchange rate regime is?

- Should Kenya abandon the Shilling either for a common East African or a Pan-African currency?

- When should fuel be included and in the measure of core inflation in Kenya and when should it be excluded?

More Blogs

Gen Z Collective Action on Taxation and Economic Policy.

Introduction The Finance Bill 2024 in Kenya sparked a wave of collective action primarily driven by Gen Z, marking a significant moment for youth engagement in Kenyan politics. This younger generation, known for their digital fluency and facing bleak economic prospects, utilised social media platforms to voice their discontent and mobilise protests against the proposed […]

Important dates and Citizen Concerns During Budget Planning Phase for Fiscal Year 2025/2026

The Budget formulation and preparation process in Kenya is guided by a budget calendar which indicates the timelines for key activities issued in accordance with Section 36 of the Public Finance Management Act, 2012.These provide guidelines on the procedures for preparing the subsequent financial year and the Medium-Term budget forecasts. The Launch of the budget […]

Adjusted IMF Program Demands on Kenya

In the IMF WEO published yesterday, the IMF elaborated its macroeconomic framework for the ongoing IMF program. The numbers clarify how the program, derailed by the mid-year Gen-Z protests, has been adjusted to make possible the Board meeting for the combined 7th and 8th Reviews scheduled for October 30. The adjustments, unfortunately, again raise profound […]

What does the Nobel Prize in Economics 2024 mean for Constitution Implementation in Kenya?

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for their research on how a country’s institutions significantly impact its long-term economic success.[1] Their work emphasizes that it’s not just about a nation’s resources or technological advancements but rather the “rules of the game” that truly matter. Countries with […]

Highlights of The World Trade Report 2024.

The World Trade Report 2024 was launched at the start of the WTO Public Forum 2024 in Geneva titled “Trade and Inclusiveness: How to Make Trade Work for All”[1], and this blog will seek to highlight some of the most profound insights. The report delves into the crucial relationship between international trade and inclusive economic […]