NSSF Act 2013, Third Schedule: Ambiguity, Interpretation Challenges and Implications for Implementation

Category: Social security fund

By: Fiona Okadia,

Background

The National Social Security Fund (NSSF) was established in Kenya in 1965 under the National Social Security Fund Act (Cap 258). As a crucial institution in the country, the NSSF aimed to provide social security benefits to employees obligated to contribute Ksh 200, with the employer matching this contribution, totalling Ksh 400.

A significant legislative change occurred with the enactment of the NSSF Act, 2013 to enhance and rejuvenate the Fund. The NSSF Act, 2013 brought about substantial modifications to the contribution structure. This law mandates employees to contribute six percent of their pensionable earnings, while employers were required to match this contribution.

Despite the well-intentioned amendments of increasing both employee and national savings, the implementation of the NSSF Act of 2013 faced a series of legal challenges. Several petitions were filed questioning the constitutionality and fairness of the new provisions. These legal challenges resulted in delays that postponed the effective implementation of the Act from the initially intended date of 10th January 2014 to February 2023.

Introduction

On January 11th, 2024, the NSSF issued a Public Notice through the daily newspapers, offering insights into the forthcoming changes in the lower and upper limits of NSSF contributions, set to take effect from February 2024. It is evident, however, that there is a slight difference in adherence to the NSSF Act when it comes to determining the upper limit, a matter that is explored in this blog piece. Furthermore, this piece aims to underscore the ambiguity surrounding the interpretation of the upper limit, emphasizing the necessity for clarity on this matter.

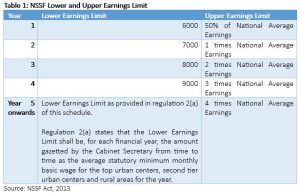

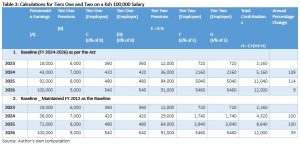

The NSSF Act, 2013, Third Schedule incorporates a table outlining the progression of contribution rates. According to this schedule, the Lower Earnings Limit and the Upper Earnings Limit are determined as shown in Table 1 for the first four years post the commencement date. Subsequently, starting from the fifth year, the Lower Earnings Limit for each financial year will be the amount published by the Cabinet Secretary responsible for matters relating to social security as the average statutory minimum monthly basic wage in the top urban centers, second-tier urban centers, and rural areas. Simultaneously, the Upper Earnings Limit for each financial year will be four times the National Average Earnings. All calculations by this Act, particularly those based on Table 1, shall be expressed in Kenyan shillings.

Interpretation as Per the NSSF Act, 2013

For interpretation purposes, “National Average Earnings” refers to the average wage earnings per employee for each financial year, as published by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics in the Economic Survey for the prior year. Additionally, the “Upper Earnings Limit,” as per the Third Schedule for each financial year, signifies earnings equivalent to four times the National Average Earnings.

Furthermore, “Tier I Contributions” denote contributions in any given month related to Pensionable Earnings up to the Lower Earnings Limit. On the other hand, “Tier II Contributions” represent contributions in any month in respect of Pensionable Earnings exceeding the Lower Earnings Limit.

Ambiguity and Interpretations of the Upper Limit

Notably, this section indeed offers guidance on the contributions and the upper limit. This stems from an examination of data concerning average wage earnings in the formal sector, sourced from various Economic Surveys for the financial years published by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics as expected by the NSSF Act, 2013.

- What Constitutes the National Average Earnings

Arithmetically, the average national earnings are usually calculated by summing up the total income across all sectors and dividing that sum by the total number of employees. KNBS employs this method to ascertain the formal national average earnings, encompassing both the public and private sectors.

For this, the concept of what constitutes average wage earnings is clear. However, there is a need for a clear delineation in the Act regarding whether the average earnings should be nominal or real (account for inflation), as the figures utilized by NSSF are based on the nominal. This clarification is crucial because KNBS provides both of the data.

The choice of the system of measurement used to determine the national average earnings can significantly impact individual contributions. For example, in the fiscal year 2023, if the upper limit for contributions was based on the real average monthly national earnings of Ksh 27,764, with the contribution set at 50% of this figure, the upper earnings threshold would be Ksh 13,882 (rounded off to Ksh 14,000).

In this scenario, individuals contributing to the NSSF would be required to contribute Ksh 1,560. This amount stands at Ksh 600 less than the contribution required under the previous system in the fiscal year 2023. This difference in contribution highlights the direct correlation between the chosen metric for average earnings and the financial obligations placed on contributors as one will read throughout the blog piece.

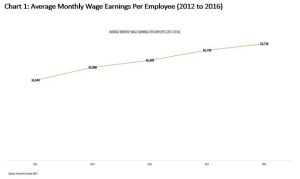

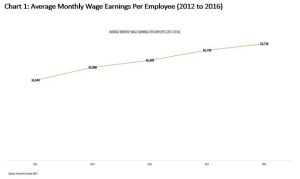

Chart 1 illustrates the progression of national average earnings from 2012 to 2016, indicating a notable increase of 46%.

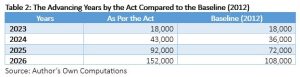

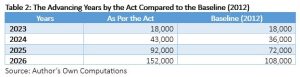

Table 2 displays the variance between the upper limits for the advancing years as per the Act compared to computation using the 2012 average monthly wage earnings as the Baseline, as utilized by NSSF in its latest publications. Considering the average wage earnings depicted in Chart 1, the projected upper limits for 2023, 2024, 2025, and 2026 would have been Ksh 18,000, Ksh 43,000, Ksh 92,000, and Ksh 152,000, respectively. This calculation is based on the Act’s definition of “National Average Earnings,” which refers to the average wage earnings per employee, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics Economic Survey of the preceding year. Consequently, data from 2013 to 2015 for the formal sector would have been employed.

2. Progressive Years Upper Limits

In 2024, the second year of implementation, the average monthly national earnings to be used should have been those published for 2013, following the trend of using the prior year’s data, resulting in Ksh 43,000. This, in conjunction with the instructions from Table 1, would have established the upper limit at Ksh 43,000.

For 2026, the Act specifies that the upper limit should be four times the national monthly average earnings. Using the average monthly wage earnings from 2016, which amounted to Ksh 53,736, the calculated upper limit would be Ksh 152,000.

As for the baseline, in this case is when NSSF has maintained the average monthly wage earnings for 2012 as the foundational value. Each year, following the third schedule, this figure is multiplied by the suggested multiplier.

Based on the above, it is clear that NSSF went with the baseline numbers as opposed to following the regulations. This is because, for the second year of implementation, the upper limit has been set at Ksh 36,000. This deviation contradicts the interpretation outlined in the Act, potentially motivated by an intention to protect higher-salaried employees earning above Ksh 36,000 from facing substantially increased contributions. While this approach may serve as a safeguard, it still runs afoul of the Act, as it lacks a provision granting discretionary powers for such deviations.

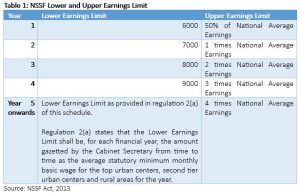

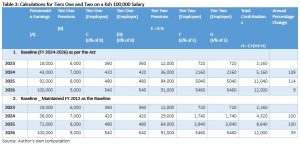

The initial query in this regard is whether NSSF will adhere to the FY 2012 baseline for the third, fourth, and fifth years, thereby establishing an upper limit of Ksh 72,000, Ksh 108,000, and Ksh 144,000 for years three, four, and five, respectively or they will decide to adjust and follow the regulations. This is because there are implications for the savings contributions. For instance, if the Act was followed then the contributions for year two would have been Ksh 5,160 instead of Ksh 4,320 for both the employee and employer as illustrated in Table 3 below implying that over four years, the contribution would have escalated by 456%, reaching Ksh 12,000. In the third year, with the National average income projected at Ksh 50,749, three times this amount would be Ksh 152,247.9, surpassing the Ksh 100,000 gross salary. Consequently, the pensionable income would be capped at Ksh 100,000. This signifies that higher-income earners will have their NSSF contributions double annually in comparison to lower-income earners until their pensionable income aligns with their gross salaries.

Also, to emphasize the need for careful consideration and potential adjustments in the NSSF Act to align with the chosen implied method or to reword the NSSF Act, 2013 to align with the already adopted mechanism of using the average wage earnings for the initial year.

This analysis reveals that the overall increment over the four years remains consistent at 456%, irrespective of the upper limit employed. However, the annual increment varies, as demonstrated in Table 3. Opting for the FY 2012 baseline appears to yield a smoother and less pronounced annual increment compared to utilizing the average wage earnings from FY 2014 to 2016. This suggests that the NSSF may have aimed for a gradual approach, ultimately achieving the same Ksh 12,000 contributions, for instance, for an individual earning Ksh 100,000.

3.What is the Rationale Behind Not Utilizing More Recent Data?

When dealing with data, it’s common practice to utilize the most recently published information. However, this standard was not followed upon the implementation of the NSSF Act. In this section, I explore how contributions would have appeared if the latest available data had been applied.

In the fiscal year 2021, the annual average earnings within the formal sector amounted to Ksh 827,295.2, translating to a monthly average of Ksh 68,941.27. If this figure had been employed, the upper limit for the first year would have been Ksh 34,470.63, deviating from the stipulated Ksh 18,000 which is much lower.

The choice of 2021 data is justified by the fact that the data for 2022 was released on May 3rd, 2023 by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, at which point the new NSSF rates had already taken effect, necessitating the use of the 2021 data.

According to the initial plan, the upper limit was intended to be 50% of the national average wage earnings. Consequently, individuals with a gross salary surpassing Ksh 34,000 would have been contributing Ksh 4,080 instead of the designated Ksh 2,160. In the second year, utilizing 2022 average wages of Ksh 72,000, the contribution would have been Ksh 8,640 for an employee earning above Ksh 72,000. This marked increment, from the preceding Ksh 400, represents a considerable contrast to what was implemented in 2023.

From the two distinct methods of calculating the upper limit, NSSF chose the approach that would result in balancing the increased contributions with a phased and considerate approach. This decision takes into consideration the financial capacities of contributors, particularly in light of upcoming adjustments to statutory deductions, such as those for the Social Health Insurance Fund, set to be increased and updated from the National Health Insurance Fund. Additionally, the introduction of the National Housing Development Fund in the financial year 2023 adds another layer of financial responsibility for employees. Simultaneously, implementing all these changes would have led to a substantial surge in the overall cost of employment.

Hence, due to the delay caused by court proceedings, there have been repercussions on both individual and national savings. This has resulted in lost opportunities for incremental contributions to NSSF. However, a more detailed examination of this matter will be covered in a subsequent blog post.

Effects

While the Act is clear, the ambiguity lies in the interpretations of the national average earnings that are to be used to determine the upper limits. We further, engage in the potential implications of this increment upward alteration in the contributions to the NSSF.

Firstly, an elevation in contribution amounts would lead to a notable surge in the overall annual collection by the NSSF. This, over the long term, plays a pivotal role in enlarging the size of the fund. Beyond its immediate impact on the NSSF’s financial health, this growth has broader implications, influencing national savings as a whole while at the same time providing funds that can be used to finance economic development.

Secondly, such an increase in contributions could lead to a rise in the overall cost of employment. Employers, who typically share the burden of social security contributions with employees, might experience an elevated financial obligation due to the higher contribution rates. Conversely, the net income of employees is set to decrease further each year further affecting the disposable income of those who contribute to this fund.

Thirdly, individuals contributing to the NSSF may see an increase in their pension savings. This could be particularly significant for those who rely solely on the NSSF for their retirement benefits or do not have a private pension savings scheme. The higher contribution amounts would contribute to an accumulation of more substantial retirement savings over time.

I had previously discussed these three effects in a prior article here and I believe that it is important to consider the implications of such alterations on both employers and employees and their long-term financial well-being.

Finally, the overarching objective appears to be augmenting individual pension contributions, indicating a progression in that aspect. Nevertheless, when expanding the pool of funds contributed to the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), it becomes apparent that individuals with higher incomes contribute more than their lower-income counterparts. Although this aligns with the principle of progression based on absolute contribution figures, a disparity emerges in the impact on net income, notably between high and low earners. As a result, if the intention is to embody a Progressive Contribution model, it inadvertently places the low-income earner at a disadvantage, particularly during the initial stages of implementation.

To illustrate this point, let’s consider two employees, one earning Ksh 100,000 and the other Ksh 36,000. The individual earning Ksh 36,000 experiences a 2% reduction in net income, whereas the one earning Ksh 100,000 sees a 1% reduction. Surprisingly, despite the percentage difference, both individuals experience an equal reduction in net income, amounting to Ksh 756.

This observation reveals that the current contribution model displays regressive tendencies during the initial five years, disproportionately affecting lower-income earners who endure more significant losses in terms of net income. Importantly, over the long term, higher-income earners stand to gain considerably more benefits, given that annuities are calculated based on individual contribution amounts.

Furthermore, the likelihood that those with higher incomes also have additional private pension arrangements accentuates the perception that the current system will benefit high-income earners to a greater extent than their lower-income counterparts.

Conclusion

In light of the anticipated significant surge in the funds managed by the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) over the next four years, there is a pressing concern among contributors regarding their funds in terms of investment returns and accessing the funds upon maturity. The ambiguity surrounding the interpretation of the NSSF Act, particularly the Third Schedule, has implications for lost contributions, fund growth, and the impact of inflation on individual savings.

To address this concern, I strongly advocate for the adoption of a more flexible approach that directly addresses the contributor’s worries. Drawing inspiration from provident funds, the NSSF should consider introducing features that empower contributors with greater control and choices concerning their contributions and withdrawals. This proposed flexibility is not only a response to the lack of confidence in the current system but also a proactive measure to ensure contributors can fully leverage the anticipated growth of the fund.

Furthermore, as the NSSF experiences this surge in funds, it is crucial to enhance the investment options available to contributors. A clearer and more diversified range of investment choices would not only potentially increase returns for contributors but also position the NSSF as a more competitive player against private-sector alternatives. This strategic allocation of funds could address the lost contribution concerns raised earlier and provide contributors with more confidence in the fund’s ability to navigate economic factors such as inflation.

More Blogs

Adjusted IMF Program Demands on Kenya

In the IMF WEO published yesterday, the IMF elaborated its macroeconomic framework for the ongoing IMF program. The numbers clarify how the program, derailed by the mid-year Gen-Z protests, has been adjusted to make possible the Board meeting for the combined 7th and 8th Reviews scheduled for October 30. The adjustments, unfortunately, again raise profound […]

What does the Nobel Prize in Economics 2024 mean for Constitution Implementation in Kenya?

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for their research on how a country’s institutions significantly impact its long-term economic success.[1] Their work emphasizes that it’s not just about a nation’s resources or technological advancements but rather the “rules of the game” that truly matter. Countries with […]

Highlights of The World Trade Report 2024.

The World Trade Report 2024 was launched at the start of the WTO Public Forum 2024 in Geneva titled “Trade and Inclusiveness: How to Make Trade Work for All”[1], and this blog will seek to highlight some of the most profound insights. The report delves into the crucial relationship between international trade and inclusive economic […]

The Grounds to Repeal the Price Control Act of 2011

The Price Control Act of 2011, with its imposition of price ceilings on essential goods, represents a significant intervention in the natural forces of supply and demand that govern a free market. The Act empowers the Minister to control the prices of essential goods, preventing them from becoming unaffordable. The Act outlines a specific mechanism […]

Why is Kenya’s Fiscal Consolidation Agenda Facing Failure?

The earliest proposition of fiscal consolidation can be traced back to the Keynesian theory which argues that fiscal austerity measures reduce growth and increases unemployment through aggregate demand effects. According to this theory, government undertaking contractionary fiscal policies of either reducing government spending or increasing tax rates, will eventually suffer a reduction in aggregate demand […]

NSSF Act 2013, Third Schedule: Ambiguity, Interpretation Challenges and Implications for Implementation

| Post date: Tue, Jan 23, 2024 |

| Category: Social security fund |

| By: Fiona Okadia, |

Background

The National Social Security Fund (NSSF) was established in Kenya in 1965 under the National Social Security Fund Act (Cap 258). As a crucial institution in the country, the NSSF aimed to provide social security benefits to employees obligated to contribute Ksh 200, with the employer matching this contribution, totalling Ksh 400.

A significant legislative change occurred with the enactment of the NSSF Act, 2013 to enhance and rejuvenate the Fund. The NSSF Act, 2013 brought about substantial modifications to the contribution structure. This law mandates employees to contribute six percent of their pensionable earnings, while employers were required to match this contribution.

Despite the well-intentioned amendments of increasing both employee and national savings, the implementation of the NSSF Act of 2013 faced a series of legal challenges. Several petitions were filed questioning the constitutionality and fairness of the new provisions. These legal challenges resulted in delays that postponed the effective implementation of the Act from the initially intended date of 10th January 2014 to February 2023.

Introduction

On January 11th, 2024, the NSSF issued a Public Notice through the daily newspapers, offering insights into the forthcoming changes in the lower and upper limits of NSSF contributions, set to take effect from February 2024. It is evident, however, that there is a slight difference in adherence to the NSSF Act when it comes to determining the upper limit, a matter that is explored in this blog piece. Furthermore, this piece aims to underscore the ambiguity surrounding the interpretation of the upper limit, emphasizing the necessity for clarity on this matter.

The NSSF Act, 2013, Third Schedule incorporates a table outlining the progression of contribution rates. According to this schedule, the Lower Earnings Limit and the Upper Earnings Limit are determined as shown in Table 1 for the first four years post the commencement date. Subsequently, starting from the fifth year, the Lower Earnings Limit for each financial year will be the amount published by the Cabinet Secretary responsible for matters relating to social security as the average statutory minimum monthly basic wage in the top urban centers, second-tier urban centers, and rural areas. Simultaneously, the Upper Earnings Limit for each financial year will be four times the National Average Earnings. All calculations by this Act, particularly those based on Table 1, shall be expressed in Kenyan shillings.

Interpretation as Per the NSSF Act, 2013

For interpretation purposes, “National Average Earnings” refers to the average wage earnings per employee for each financial year, as published by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics in the Economic Survey for the prior year. Additionally, the “Upper Earnings Limit,” as per the Third Schedule for each financial year, signifies earnings equivalent to four times the National Average Earnings.

Furthermore, “Tier I Contributions” denote contributions in any given month related to Pensionable Earnings up to the Lower Earnings Limit. On the other hand, “Tier II Contributions” represent contributions in any month in respect of Pensionable Earnings exceeding the Lower Earnings Limit.

Ambiguity and Interpretations of the Upper Limit

Notably, this section indeed offers guidance on the contributions and the upper limit. This stems from an examination of data concerning average wage earnings in the formal sector, sourced from various Economic Surveys for the financial years published by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics as expected by the NSSF Act, 2013.

- What Constitutes the National Average Earnings

Arithmetically, the average national earnings are usually calculated by summing up the total income across all sectors and dividing that sum by the total number of employees. KNBS employs this method to ascertain the formal national average earnings, encompassing both the public and private sectors.

For this, the concept of what constitutes average wage earnings is clear. However, there is a need for a clear delineation in the Act regarding whether the average earnings should be nominal or real (account for inflation), as the figures utilized by NSSF are based on the nominal. This clarification is crucial because KNBS provides both of the data.

The choice of the system of measurement used to determine the national average earnings can significantly impact individual contributions. For example, in the fiscal year 2023, if the upper limit for contributions was based on the real average monthly national earnings of Ksh 27,764, with the contribution set at 50% of this figure, the upper earnings threshold would be Ksh 13,882 (rounded off to Ksh 14,000).

In this scenario, individuals contributing to the NSSF would be required to contribute Ksh 1,560. This amount stands at Ksh 600 less than the contribution required under the previous system in the fiscal year 2023. This difference in contribution highlights the direct correlation between the chosen metric for average earnings and the financial obligations placed on contributors as one will read throughout the blog piece.

Chart 1 illustrates the progression of national average earnings from 2012 to 2016, indicating a notable increase of 46%.

Table 2 displays the variance between the upper limits for the advancing years as per the Act compared to computation using the 2012 average monthly wage earnings as the Baseline, as utilized by NSSF in its latest publications. Considering the average wage earnings depicted in Chart 1, the projected upper limits for 2023, 2024, 2025, and 2026 would have been Ksh 18,000, Ksh 43,000, Ksh 92,000, and Ksh 152,000, respectively. This calculation is based on the Act’s definition of “National Average Earnings,” which refers to the average wage earnings per employee, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics Economic Survey of the preceding year. Consequently, data from 2013 to 2015 for the formal sector would have been employed.

2. Progressive Years Upper Limits

In 2024, the second year of implementation, the average monthly national earnings to be used should have been those published for 2013, following the trend of using the prior year’s data, resulting in Ksh 43,000. This, in conjunction with the instructions from Table 1, would have established the upper limit at Ksh 43,000.

For 2026, the Act specifies that the upper limit should be four times the national monthly average earnings. Using the average monthly wage earnings from 2016, which amounted to Ksh 53,736, the calculated upper limit would be Ksh 152,000.

As for the baseline, in this case is when NSSF has maintained the average monthly wage earnings for 2012 as the foundational value. Each year, following the third schedule, this figure is multiplied by the suggested multiplier.

Based on the above, it is clear that NSSF went with the baseline numbers as opposed to following the regulations. This is because, for the second year of implementation, the upper limit has been set at Ksh 36,000. This deviation contradicts the interpretation outlined in the Act, potentially motivated by an intention to protect higher-salaried employees earning above Ksh 36,000 from facing substantially increased contributions. While this approach may serve as a safeguard, it still runs afoul of the Act, as it lacks a provision granting discretionary powers for such deviations.

The initial query in this regard is whether NSSF will adhere to the FY 2012 baseline for the third, fourth, and fifth years, thereby establishing an upper limit of Ksh 72,000, Ksh 108,000, and Ksh 144,000 for years three, four, and five, respectively or they will decide to adjust and follow the regulations. This is because there are implications for the savings contributions. For instance, if the Act was followed then the contributions for year two would have been Ksh 5,160 instead of Ksh 4,320 for both the employee and employer as illustrated in Table 3 below implying that over four years, the contribution would have escalated by 456%, reaching Ksh 12,000. In the third year, with the National average income projected at Ksh 50,749, three times this amount would be Ksh 152,247.9, surpassing the Ksh 100,000 gross salary. Consequently, the pensionable income would be capped at Ksh 100,000. This signifies that higher-income earners will have their NSSF contributions double annually in comparison to lower-income earners until their pensionable income aligns with their gross salaries.

Also, to emphasize the need for careful consideration and potential adjustments in the NSSF Act to align with the chosen implied method or to reword the NSSF Act, 2013 to align with the already adopted mechanism of using the average wage earnings for the initial year.

This analysis reveals that the overall increment over the four years remains consistent at 456%, irrespective of the upper limit employed. However, the annual increment varies, as demonstrated in Table 3. Opting for the FY 2012 baseline appears to yield a smoother and less pronounced annual increment compared to utilizing the average wage earnings from FY 2014 to 2016. This suggests that the NSSF may have aimed for a gradual approach, ultimately achieving the same Ksh 12,000 contributions, for instance, for an individual earning Ksh 100,000.

3.What is the Rationale Behind Not Utilizing More Recent Data?

When dealing with data, it’s common practice to utilize the most recently published information. However, this standard was not followed upon the implementation of the NSSF Act. In this section, I explore how contributions would have appeared if the latest available data had been applied.

In the fiscal year 2021, the annual average earnings within the formal sector amounted to Ksh 827,295.2, translating to a monthly average of Ksh 68,941.27. If this figure had been employed, the upper limit for the first year would have been Ksh 34,470.63, deviating from the stipulated Ksh 18,000 which is much lower.

The choice of 2021 data is justified by the fact that the data for 2022 was released on May 3rd, 2023 by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, at which point the new NSSF rates had already taken effect, necessitating the use of the 2021 data.

According to the initial plan, the upper limit was intended to be 50% of the national average wage earnings. Consequently, individuals with a gross salary surpassing Ksh 34,000 would have been contributing Ksh 4,080 instead of the designated Ksh 2,160. In the second year, utilizing 2022 average wages of Ksh 72,000, the contribution would have been Ksh 8,640 for an employee earning above Ksh 72,000. This marked increment, from the preceding Ksh 400, represents a considerable contrast to what was implemented in 2023.

From the two distinct methods of calculating the upper limit, NSSF chose the approach that would result in balancing the increased contributions with a phased and considerate approach. This decision takes into consideration the financial capacities of contributors, particularly in light of upcoming adjustments to statutory deductions, such as those for the Social Health Insurance Fund, set to be increased and updated from the National Health Insurance Fund. Additionally, the introduction of the National Housing Development Fund in the financial year 2023 adds another layer of financial responsibility for employees. Simultaneously, implementing all these changes would have led to a substantial surge in the overall cost of employment.

Hence, due to the delay caused by court proceedings, there have been repercussions on both individual and national savings. This has resulted in lost opportunities for incremental contributions to NSSF. However, a more detailed examination of this matter will be covered in a subsequent blog post.

Effects

While the Act is clear, the ambiguity lies in the interpretations of the national average earnings that are to be used to determine the upper limits. We further, engage in the potential implications of this increment upward alteration in the contributions to the NSSF.

Firstly, an elevation in contribution amounts would lead to a notable surge in the overall annual collection by the NSSF. This, over the long term, plays a pivotal role in enlarging the size of the fund. Beyond its immediate impact on the NSSF’s financial health, this growth has broader implications, influencing national savings as a whole while at the same time providing funds that can be used to finance economic development.

Secondly, such an increase in contributions could lead to a rise in the overall cost of employment. Employers, who typically share the burden of social security contributions with employees, might experience an elevated financial obligation due to the higher contribution rates. Conversely, the net income of employees is set to decrease further each year further affecting the disposable income of those who contribute to this fund.

Thirdly, individuals contributing to the NSSF may see an increase in their pension savings. This could be particularly significant for those who rely solely on the NSSF for their retirement benefits or do not have a private pension savings scheme. The higher contribution amounts would contribute to an accumulation of more substantial retirement savings over time.

I had previously discussed these three effects in a prior article here and I believe that it is important to consider the implications of such alterations on both employers and employees and their long-term financial well-being.

Finally, the overarching objective appears to be augmenting individual pension contributions, indicating a progression in that aspect. Nevertheless, when expanding the pool of funds contributed to the National Social Security Fund (NSSF), it becomes apparent that individuals with higher incomes contribute more than their lower-income counterparts. Although this aligns with the principle of progression based on absolute contribution figures, a disparity emerges in the impact on net income, notably between high and low earners. As a result, if the intention is to embody a Progressive Contribution model, it inadvertently places the low-income earner at a disadvantage, particularly during the initial stages of implementation.

To illustrate this point, let’s consider two employees, one earning Ksh 100,000 and the other Ksh 36,000. The individual earning Ksh 36,000 experiences a 2% reduction in net income, whereas the one earning Ksh 100,000 sees a 1% reduction. Surprisingly, despite the percentage difference, both individuals experience an equal reduction in net income, amounting to Ksh 756.

This observation reveals that the current contribution model displays regressive tendencies during the initial five years, disproportionately affecting lower-income earners who endure more significant losses in terms of net income. Importantly, over the long term, higher-income earners stand to gain considerably more benefits, given that annuities are calculated based on individual contribution amounts.

Furthermore, the likelihood that those with higher incomes also have additional private pension arrangements accentuates the perception that the current system will benefit high-income earners to a greater extent than their lower-income counterparts.

Conclusion

In light of the anticipated significant surge in the funds managed by the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) over the next four years, there is a pressing concern among contributors regarding their funds in terms of investment returns and accessing the funds upon maturity. The ambiguity surrounding the interpretation of the NSSF Act, particularly the Third Schedule, has implications for lost contributions, fund growth, and the impact of inflation on individual savings.

To address this concern, I strongly advocate for the adoption of a more flexible approach that directly addresses the contributor’s worries. Drawing inspiration from provident funds, the NSSF should consider introducing features that empower contributors with greater control and choices concerning their contributions and withdrawals. This proposed flexibility is not only a response to the lack of confidence in the current system but also a proactive measure to ensure contributors can fully leverage the anticipated growth of the fund.

Furthermore, as the NSSF experiences this surge in funds, it is crucial to enhance the investment options available to contributors. A clearer and more diversified range of investment choices would not only potentially increase returns for contributors but also position the NSSF as a more competitive player against private-sector alternatives. This strategic allocation of funds could address the lost contribution concerns raised earlier and provide contributors with more confidence in the fund’s ability to navigate economic factors such as inflation.

More Blogs

Adjusted IMF Program Demands on Kenya

In the IMF WEO published yesterday, the IMF elaborated its macroeconomic framework for the ongoing IMF program. The numbers clarify how the program, derailed by the mid-year Gen-Z protests, has been adjusted to make possible the Board meeting for the combined 7th and 8th Reviews scheduled for October 30. The adjustments, unfortunately, again raise profound […]

What does the Nobel Prize in Economics 2024 mean for Constitution Implementation in Kenya?

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for their research on how a country’s institutions significantly impact its long-term economic success.[1] Their work emphasizes that it’s not just about a nation’s resources or technological advancements but rather the “rules of the game” that truly matter. Countries with […]

Highlights of The World Trade Report 2024.

The World Trade Report 2024 was launched at the start of the WTO Public Forum 2024 in Geneva titled “Trade and Inclusiveness: How to Make Trade Work for All”[1], and this blog will seek to highlight some of the most profound insights. The report delves into the crucial relationship between international trade and inclusive economic […]

The Grounds to Repeal the Price Control Act of 2011

The Price Control Act of 2011, with its imposition of price ceilings on essential goods, represents a significant intervention in the natural forces of supply and demand that govern a free market. The Act empowers the Minister to control the prices of essential goods, preventing them from becoming unaffordable. The Act outlines a specific mechanism […]

Why is Kenya’s Fiscal Consolidation Agenda Facing Failure?

The earliest proposition of fiscal consolidation can be traced back to the Keynesian theory which argues that fiscal austerity measures reduce growth and increases unemployment through aggregate demand effects. According to this theory, government undertaking contractionary fiscal policies of either reducing government spending or increasing tax rates, will eventually suffer a reduction in aggregate demand […]